How do active agents need to be constructed in order to disable the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2? Researchers at the Paul Scherrer Institute PSI are investigating this question in cooperation with research groups around the world. Using a method that is still quite new, they are testing whether or not molecule fragments bind to important proteins of the coronavirus. They hope that the many individual pieces of information gained will yield an answer to what an effective drug would look like. The special thing about this: These binding experiments take place in the already crystallised protein. That makes the procedure quite tricky.

Protein molecules make it possible for the coronavirus to smuggle itself into the cells of our bodies and multiply explosively within them. If you block one or several of these proteins, you also block the virus. For this, you need active agents that bind firmly to those parts of the protein that are crucial for it to function. Researchers at PSI's Crystallisation Facility are working to find such potential drug candidates.

To do this, pharmaceutical companies normally investigate millions of complex substances. If a molecule is found that binds tightly to the protein, another round of hard work begins: The researchers try to grow crystals of the complex that the potential active agent has formed with the virus protein, in order to examine its structure.

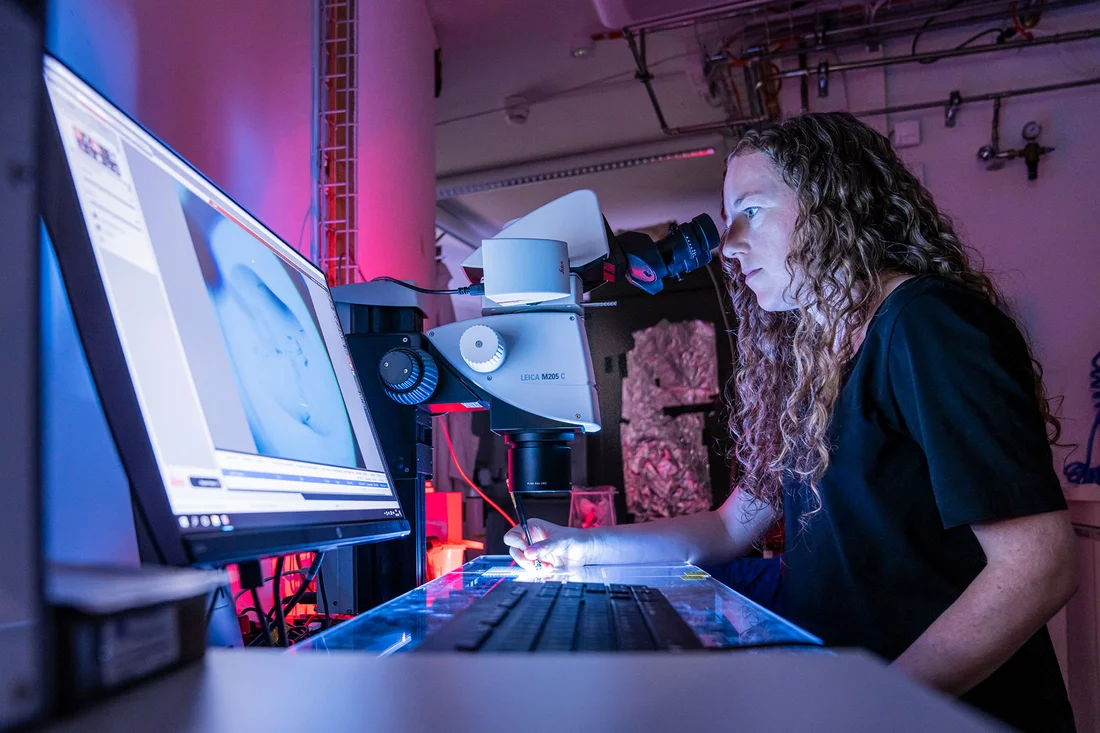

In contrast, May Sharpe and her team in the PSI Crystallisation Facility take a different path. They are applying a technique called fragment screening: "We add solutions containing fragments of molecules that are typical for promising active agents to crystals of viral protein," she explains. The fragments are much smaller than the actual compounds that might later come onto the market as active ingredients. Then the researchers let the mixture of crystals and molecule fragments stand for a few hours or even overnight; during this time, the crystal can more or less soak up the fragment solution. Finally, the crystals are fished out of the liquid and X-rayed at the Swiss Light Source SLS. On the basis of the diffraction pattern this creates, a back-calculation of the three-dimensional structure of the protein complex can be made – showing the bound fragments in the middle.

"This enables us to see not only whether the fragments have bound to the protein, but also how," Sharpe says. "So we are not finding any actual drugs, but we are slowly feeling our way towards the structure a drug must have to be able to help." Entire libraries of such molecule fragments exist, which researchers are testing bit by bit. During the process of exposing crystals to the solution, some fragments form bonds of different strengths with the proteins. Then, in a second run, new molecules that already combine proven characteristics can be synthesised and tried out.

A close look at coronavirus

May Sharpe and her team are collaborating with researchers from all over the world to study several proteins of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus. “For example, we've already been working for a long time with Professor Sheng Cui from the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, an absolute expert on coronaviruses," Sharpe explains. "Now we can build on that."

One of the proteins the PSI researchers are examining is a helicase. This enzyme ensures that the genetic material of the virus can multiply in the cells of an infected person. Another protein, the 3CL protease, cuts the virus's own proteins after replication in such a way that new, reproducible coronaviruses are created.

In cooperation with the group led by Apirat Chaikuad from the Institute for Pharmaceutical Chemistry at the Goethe University in Frankfurt, PSI is also investigating the so-called macrodomain, another coronavirus protein. Normally, if a person is infected with a virus, the body's cells quickly intervene: They mark foreign proteins that could pose a threat with something similar to a red flag. This is how the immune system recognises and gets rid of them. The coronavirus has armed itself against this. The macrodomain cuts this marker off again and thus fools the immune system, which no longer recognises the building blocks of the virus as foreign to the body. If the macrodomain can be blocked with the aid of drugs, the human body may be able to recognise the virus proteins as intruders and defend itself better against the virus.

On a mini scale

To investigate these and other proteins of the coronavirus, May Sharpe first grows as many crystals of each respective protein as possible. That in itself is a challenge, because proteins are complex three-dimensional structures that are reluctant to stay together in large associations. But to test all of the molecular fragments in a library, Sharpe needs several thousand crystals at once. When the crystals are finally available, a robot helps to carry out the countless test series that now need to be run.

Even a single series of experiments requires a tremendous amount of preparation. The first screening tests with proteins from SARS-CoV-2 will be ready to start soon.

Text: Paul Scherrer Institute/Brigitte Osterath

Contact

Dr. May Elizabeth Sharpe

Crystallisation Facility

Laboratory for Macromolecules and Bioimaging

Paul Scherrer Institute, Forschungsstrasse 111, 5232 Villigen PSI, Switzerland

Telephone: +41 56 310 54 37, e-mail: may.sharpe@psi.ch [English]

Further information

Copyright

PSI provides image and/or video material free of charge for media coverage of the content of the above text. Use of this material for other purposes is not permitted. This also includes the transfer of the image and video material into databases as well as sale by third parties.