Field trials show that new catalyst material for electrolysers is reliable

Efficient storage technologies are necessary if solar and wind energy is to help satisfy increased energy demands. One important approach is storage in the form of hydrogen extracted from water using solar or wind energy. This process takes place in a so-called electrolyser. Thanks to a new material developed by researchers at the Paul Scherrer Institute PSI and Empa, these devices are likely to become cheaper and more efficient in the future. The material in question works as a catalyst accelerating the splitting of water molecules: the first step in the production of hydrogen. Researchers also showed that this new material can be reliably produced in large quantities and demonstrated its performance capability within a technical electrolysis cell—the main component of an electrolyser. The results of their research have been published in the current edition of the scientific journal Nature Materials.

Since solar and wind energy is not always available, it will only contribute significantly to meeting energy demands once a reliable storage method has been developed. One promising approach to this problem is storage in the form of hydrogen. This process requires an electrolyser, which uses electricity generated by solar or wind energy to split water into hydrogen and oxygen. Hydrogen serves as an energy carrier. It can be stored in tanks and later transformed back into electrical energy with the help of fuel cells. This process can be carried out locally, in places where energy is needed such as domestic residences or fuel cell vehicles, enabling mobility without the emission of CO2.

Inexpensive and efficient

Researchers at the Paul Scherrer Institute PSI have now developed a new material that functions as a catalyst within an electrolyser and thus accelerates the splitting of water molecules: the first step in the production of hydrogen. There are currently two types of electrolysers on the market: one is efficient but expensive because its catalysts contain noble metals such as iridium. The others are cheaper but less efficient

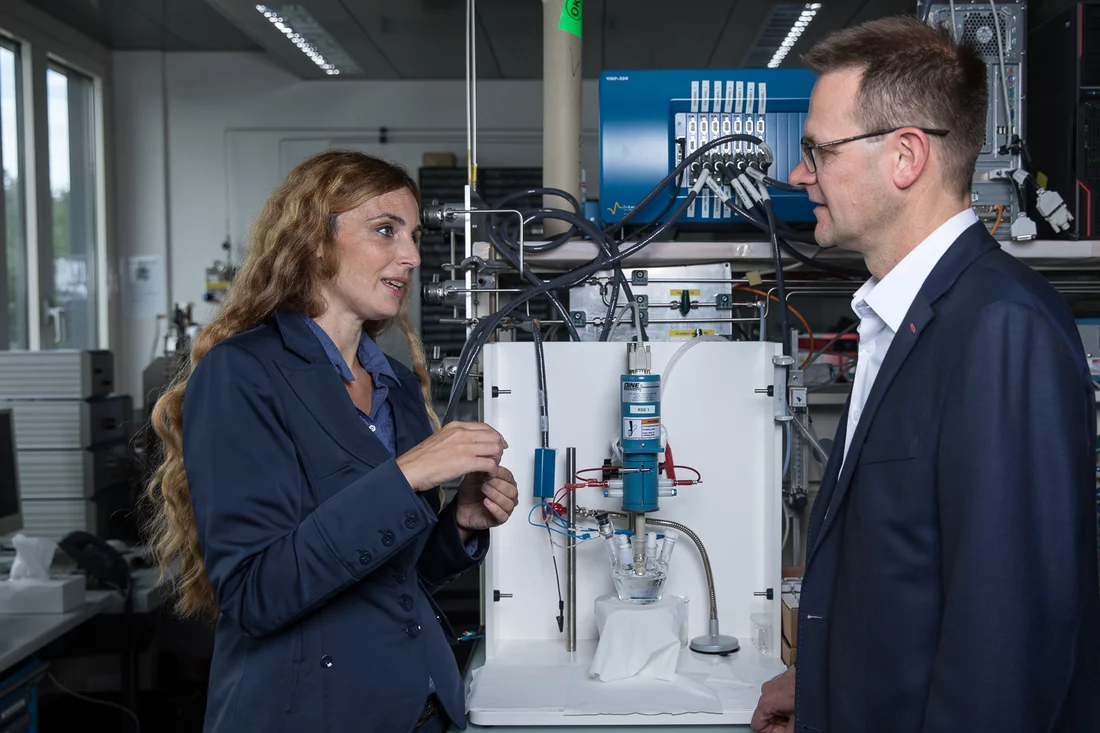

, explains Emiliana Fabbri, researcher at the Paul Scherrer Institute. We wanted to develop an efficient but less expensive catalyst that worked without using noble metals.

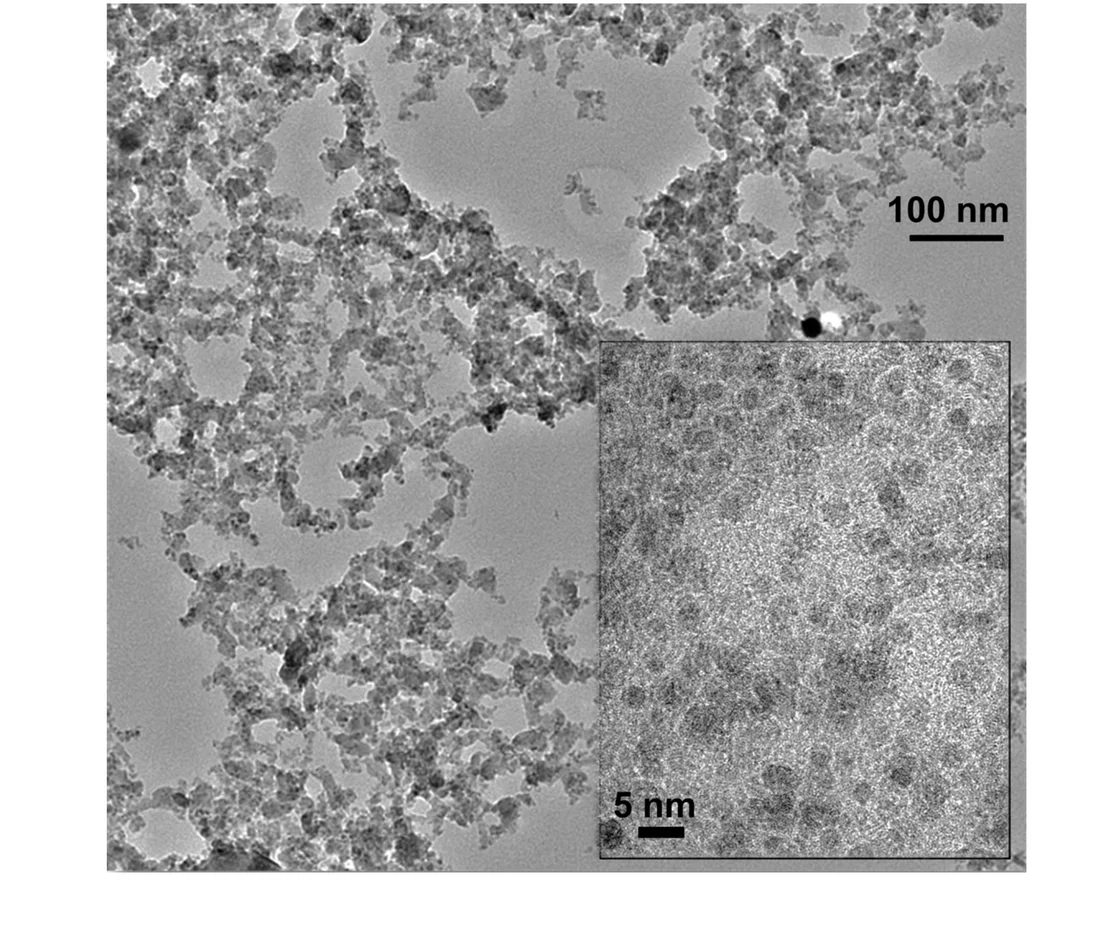

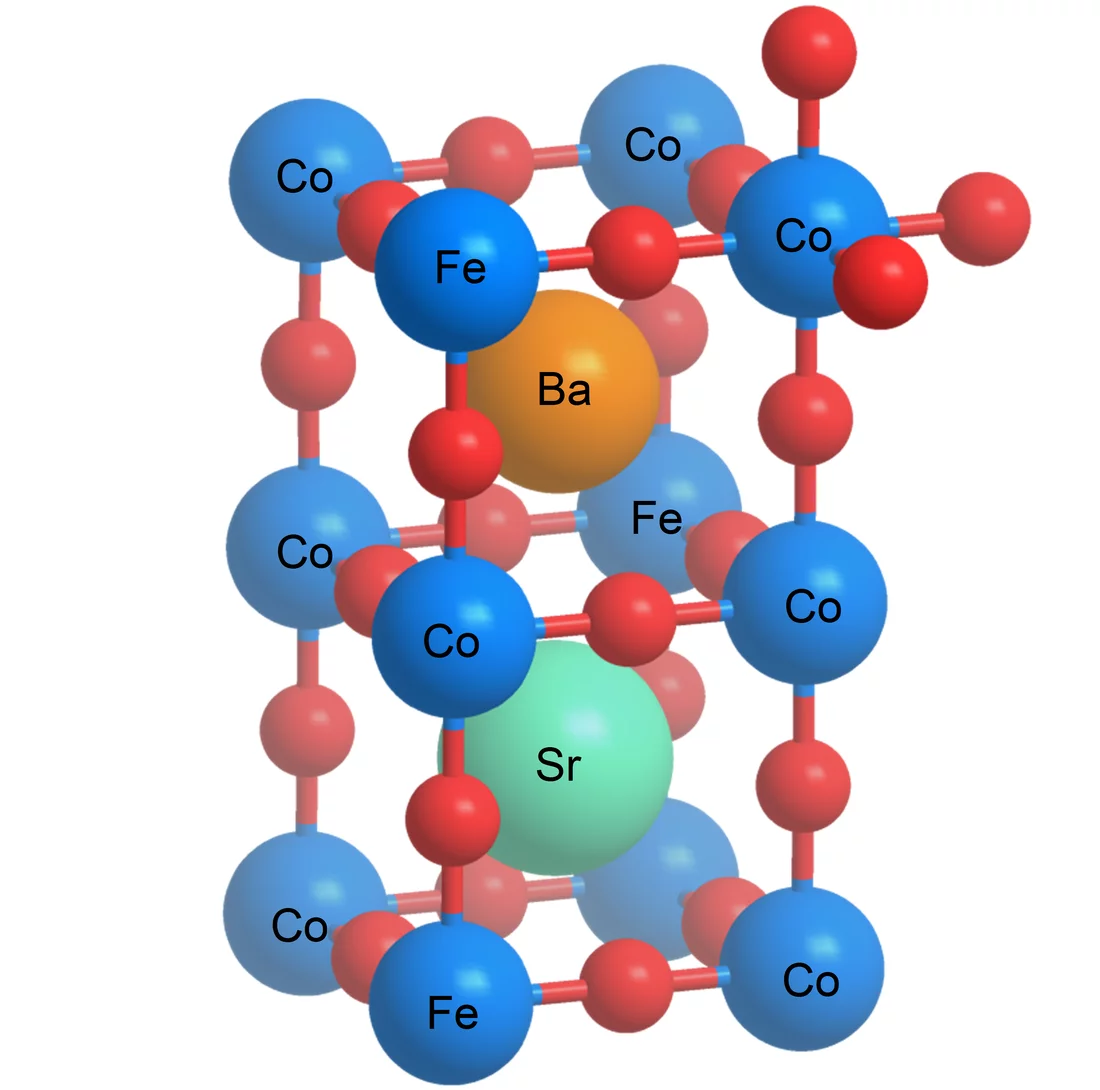

Exploring this procedure, researchers were able to use a material that had already been developed: an intricate compound of the elements barium, strontium, cobalt, iron and oxygen – a so-called perovskite. But they were the first to develop a technique enabling its production in the form of miniscule nanoparticles. This is the form required for it to function efficiently since a catalyst requires a large surface area on which many reactive centres are able to accelerate the electrochemical reaction. Once individual catalyst particles have been made as small as possible, their respective surfaces combine to create a much larger overall surface area.

Researchers used a so-called flame-spray device to produce this nanopowder: a device operated by Empa that sends the material's constituent parts through a flame where they merge and quickly solidify into small particles once they leave the flame. We had to find a way of operating the device that reliably guaranteed the solidifying of the atoms of the various elements in the right structure,

emphasizes Fabbri. We were also able to vary the oxygen content where necessary, enabling the production of different material variants.

Successful Field Tests

Researchers were able to show that these procedures work not only in the laboratory but also in practice. The production method delivers large quantities of the catalyst powder and can be made readily available for industrial use. We were eager to test the catalyst in field conditions. Of course, we have test facilities at PSI capable of examining the material but its value ultimately depends upon its suitability for industrial electrolysis cells that are used in commercial electrolysers,

says Fabbri. Researchers tested the catalyst in cooperation with an electrolyser manufacturer in the US and were able to show that the device worked more reliably with the new PSI-produced perovskite than with a conventional iridium-oxide catalyst.

Examining in Milliseconds

Researchers were also able to carry out precise experiments that provided accurate information on what happens in the new material when it is active. This involved studying the material with X-rays at PSI's Swiss Light Source SLS. This facility provides researchers with a unique measuring station capable of analysing the condition of a material over successive timespans of just 200 milliseconds. This enables us to monitor changes in the catalyst during the catalytic reaction: we can observe changes in the electronic properties or the arrangement of atoms,

says Fabbri. At other facilities, each individual measurement takes about 15 minutes, providing only an averaged image at best.

These measurements also showed how the structures of particle surfaces change when active – parts of the material become amorphous which means that the atoms in individual areas are no longer uniformly arranged. Unexpectedly, this makes the material a better catalyst.

Use in the ESI Platform

Working on the development of technological solutions for Switzerland's energy future is an essential aspect of the research carried out at PSI. To this end, PSI makes its ESI (Energy System Integration) experimental platform available to research and industry, enabling promising solutions to be tested in a variety of complex contexts. The new catalyst provides an important base for the development of a new generation of water electrolysers.

Text: Paul Scherrer Institute/Paul Piwnicki

About PSI

The Paul Scherrer Institute PSI develops, builds and operates large, complex research facilities and makes them available to the national and international research community. The institute's own key research priorities are in the fields of matter and materials, energy and environment and human health. PSI is committed to the training of future generations. Therefore about one quarter of our staff are post-docs, post-graduates or apprentices. Altogether PSI employs 2100 people, thus being the largest research institute in Switzerland. The annual budget amounts to approximately CHF 380 million. PSI is part of the ETH Domain, with the other members being the two Swiss Federal Institutes of Technology, ETH Zurich and EPFL Lausanne, as well as Eawag (Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology), Empa (Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology) and WSL (Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research).

(Last updated in May 2017)

Additional information

Experimental Platform ESI – new approaches to future energy systems: https://www.psi.ch/media/esi-platformContact

Prof. Dr. Thomas J. SchmidtHead of Electrochemistry Laboratory

Paul Scherrer Institute, 5232 Villigen PSI, Switzerland

Telephone: +41 56 310 57 65; e-mail: thomasjustus.schmidt@psi.ch

Dr. Emiliana Fabbri

Research Group Electrocatalysis and Interfaces

Electrochemistry Laboratory

Paul Scherrer Institute, 5232 Villigen PSI, Switzerland

Telephone: +41 56 310 27 95; e-mail: emiliana.fabbri@psi.ch

Original Publication

Dynamic Surface Self-Reconstruction is the Key of Highly Active Perovskite Nano-Electrocatalysts for Water SplittingEmiliana Fabbri, Maarten Nachtegaal, Tobias Binniger, Xi Cheng, Bae-Jung Kim, Julien Durst, Francesco Bozza, Thomas J. Graule, Robin Schäublin, Luke H. Wiles, Morgan Petroso, Nemanja Danilovic, Katherine Ayers, Thomas J Schmidt

Nature Materials 17 July 2017

DOI: 10.1038/nmat4938