Eighty percent of all products of the chemical industry are manufactured with catalytic processes. Catalysis is also indispensable in energy conversion and treatment of exhaust gases. It is important for these processes to run as quickly and efficiently as possible; that protects the environment while also saving time and conserving resources. Industry is always testing new substances and arrangements that could lead to new and better catalytic processes. Researchers of the Paul Scherrer Institute PSI in Villigen and ETH Zurich have now developed a method for improving the precision of such experiments, which may speed up the search for optimal solutions. At the same time, their method has enabled them to settle a scientific controversy more than 50 years old. They describe their approach in the journal Nature.

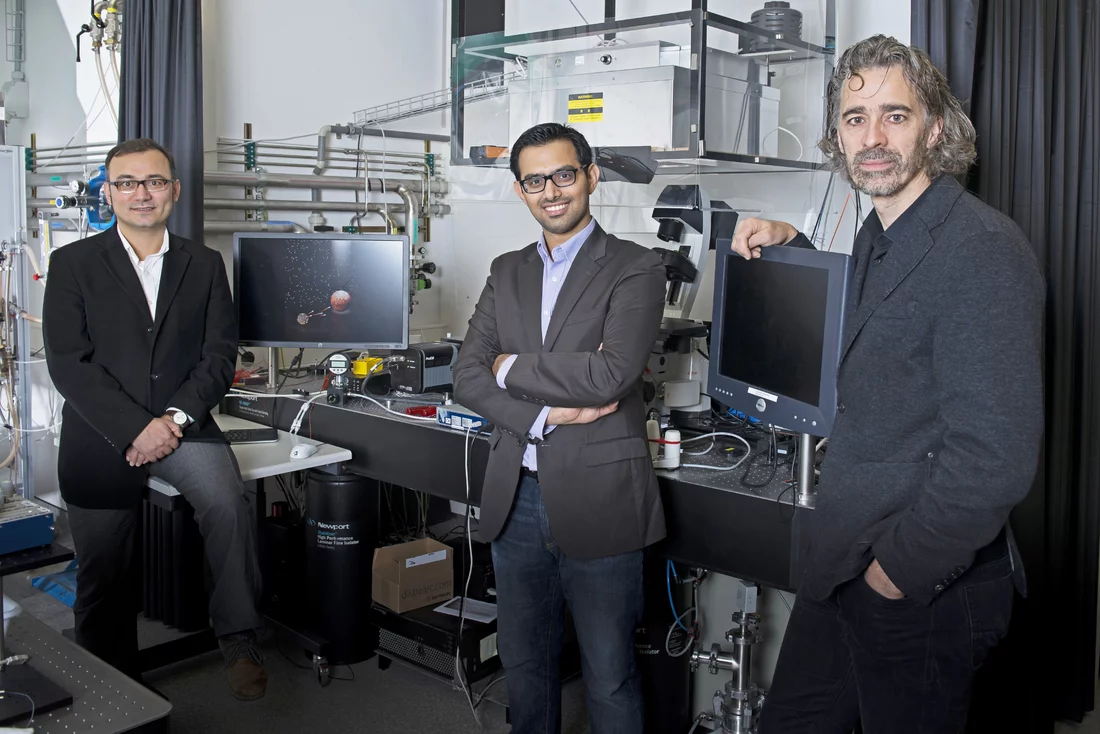

With a new process, Swiss scientists are making it easier for the chemical industry to investigate and optimise catalytic processes: We have found a way to construct catalytic model systems — that is, experimental set-ups — accurate to one nanometre and then to track the chemical reactions of individual nanoparticles

, says Waiz Karim, who is affiliated with both the Laboratory for Micro and Nanotechnology at the PSI and the Institute for Chemical and Bioengineering at ETH Zurich. This makes it possible to selectively optimise the efficiency of catalytic processes.

Catalysis is a fundamental process in chemistry: Reactions of substances are triggered or accelerated through the presence of a catalyst. It plays a major role in the manufacture of synthetic materials, acids, and other chemical products, in the treatment of exhaust gases, and in energy storage (see Background). For this reason, the industry takes a great interest in optimising catalytic processes. To do that, you need a deeper understanding of what is going on at the molecular level

, says Jeroen van Bokhoven, head of the Laboratory for Catalysis and Sustainable Chemistry at the PSI and professor of Heterogeneous Catalysis at ETH Zurich, who led the study.

Model experiment with unprecedented precision

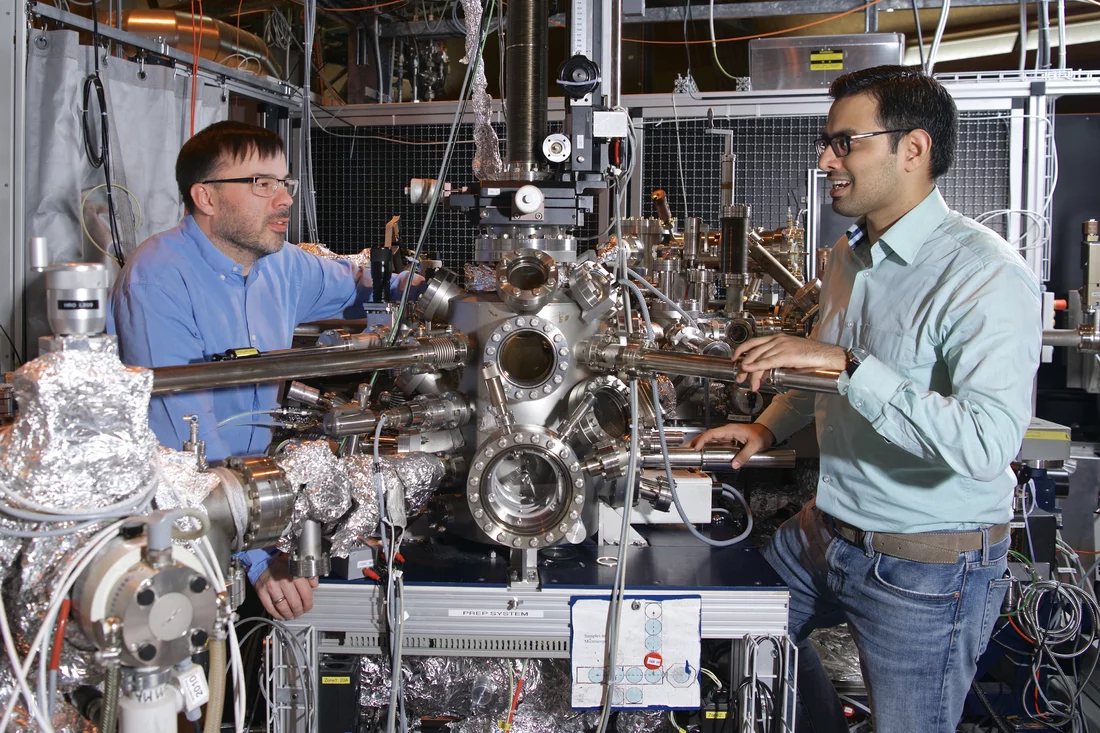

This deeper understanding can be gained through the new approach: The researchers built a model system that enables them to study catalysis in the most minute detail. The experiments were carried out mainly at the PSI, and the theoretical basis was worked out at ETH Zurich. For the model experiment the team of Karim, Ekinci and van Bokhoven used iron oxide, which was converted to iron through the addition of hydrogen and with assistance from the catalyst platinum. The platinum splits the molecular hydrogen (H2) into elemental hydrogen (H), which can more easily react with iron oxide.

The main attraction of their model: With state-of-the-art electron-beam lithography, otherwise used mainly in semiconductor technology, the researchers were able to place miniscule particles, consisting of just a few atoms each, on a support. The size of the iron oxide particles was only 60 nanometres, and the platinum particles were even smaller at 30 nanometres — about two-thousandths of the diameter of a human hair. The researchers positioned these particles in pairs on a grid-like model at 15 different distances from each other — in the first grid segment the platinum particle lay precisely on top of the iron oxide particle, and in the 15th segment, the particles lay 45 nanometres apart. In a 16th segment, the iron oxide was completely alone. Thus we were able to test 16 different situations at once and control the size and spacing of the particles with one-nanometre accuracy

, Karim explains. Then they vapourised the model with hydrogen and watched what happened.

For this observation in the molecular domain the team had, in an earlier project, employed a method called single-particle spectromicroscopy

to analyse tiny particles by means of X-rays. The instruments needed to do this are available at the Swiss Light Source SLS of the PSI, a large-scale research facility that generates high-quality X-ray light. Not only is the precision of the particle positioning new, but the correspondingly accurate observation of chemical reactions — including simultaneous observation of many particles in different situations — had not been possible before: In previous studies, placement of the nanoparticles of two different materials could be off by up to 30 nanometres

, Karim explains.

Distance-dependent spillover of hydrogen

As it turned out, though, some chemical phenomena take place on an even smaller scale. One of these is the so-called hydrogen spillover effect, which the PSI and ETH researchers examined with their new model.

This effect contributes decisively to the efficiency of catalysis with hydrogen. It was discovered in 1964 but up to now could not be understood or visualised in detail. As a result, the circumstances under which it actually occurs remained controversial.

The team of Karim, Ekinci and van Bokhoven succeeded in analysing it for the first time with the precision needed: The hydrogen molecules split as soon as they encounter the platinum particle, and then the elemental hydrogen flows down the sides onto the support material. Then they spread out all around, the way water streams out of a spring. The hydrogen atoms meet the iron oxide particles and reduce

them to iron, as researchers put it. We were able to prove that how far the hydrogen flows depends on the support material

, Karim reports. The farther it flows, the more the spillover can contribute to the catalysis. If the support consists of aluminium oxide, for example, which itself cannot be reduced, the hydrogen flows no farther than 15 nanometres. With reducible titanium oxide, in contrast, it flows over the whole surface. Clearly, for some support materials it is important how tightly the particles sit on them.

Advancing chemical science

Thus, with their new nanotechnology process, the PSI and ETH researchers have clarified the circumstances of the hydrogen spillover effect. Our method rests on three pillars

, says Jeroen van Bokhoven, the nanofabrication of the model system, the precise measurement of the chemical reactions, and last but not least the theoretical modelling: In accordance with the experiments we were able to describe the process down to the molecular level.

This, he suggests, could enable enormous advances in chemical science overall: With this we are opening up a whole new dimension for the investigation and understanding of catalytic processes. And with this understanding, industrial production processes can be optimised in a much more targeted way.

Text: Jan Berndorff

Background

In the chemical industry, catalysis is indispensable. Around 80 percent of all chemical products rely on it. Reactions between substances are triggered or accelerated by an additional substance, the catalyst. Catalysis is necessary for the production of synthetic materials, alcohol, acids, fuel, and fertilisers. It is also at work when the catalytic converter in an automobile transforms a large portion of the harmful exhaust gases into less harmful gases or when alternative energy is stored in the form of hydrogen. Most common is the so-calledheterogeneouscatalysis, meaning that the catalyst and the reacting substances are in different physical states. In most cases the catalyst is solid and is spread over the surface of a support material. The reacting agents are gaseous or liquid. Catalysis is also widespread in nature. For example, cut apples or pears turn brown because enzymes work as biocatalysts and let oxygen in the air react with the pulp of the fruit. Respiration, photosynthesis, and extracting energy from food also involve catalytic processes. Without this basic principle our whole organism — and that of other living things — simply would not work.

About PSI

The Paul Scherrer Institute PSI develops, builds and operates large, complex research facilities and makes them available to the national and international research community. The institute's own key research priorities are in the fields of matter and materials, energy and environment and human health. PSI is committed to the training of future generations. Therefore about one quarter of our staff are post-docs, post-graduates or apprentices. Altogether PSI employs 2000 people, thus being the largest research institute in Switzerland. The annual budget amounts to approximately CHF 370 million. PSI is part of the ETH Domain, with the other members being the two Swiss Federal Institutes of Technology, ETH Zurich and EPFL Lausanne, as well as Eawag (Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology), Empa (Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology) and WSL (Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research).

(Last updated in May 2016)

Contact

Prof. Dr. Jeroen van BokhovenHead of the Laboratory for Catalysis and Sustainable Chemistry, Research Area Energy and Environment

Paul Scherrer Institute, 5232 Villigen PSI, Switzerland

Telephone: +41 56 310 50 46, e-mail: jeroen.vanbokhoven@psi.ch

Professor of Heterogeneous Catalysis, ETH Zurich, 8093 Zurich, Switzerland

Telephone: +41 44 632 55 42, e-mail: jeroen.vanbokhoven@chem.ethz.ch

Original Publication

Catalyst support effects on hydrogen spilloverWaiz Karim, Clelia Spreafico, Armin Kleibert, Jens Gobrecht, Joost VandeVondele, Yasin Ekinci, Jeroen A. van Bokhoven

Nature 5 January 2017 DOI: 10.1038/nature20782