It has recently been supposed that humans could trace their ancestry back to a strange microscopic creature with a mouth and no anus. Thanks to analysis of 500 million year old fossils at the Swiss Light Source SLS, we can be relieved to find out this is not true: Saccorhytus is not a deuterostome like us, but an ecdysozoan. The findings, published today in Nature, make important amendments to the early phylogenetic tree and our understanding of how life developed.

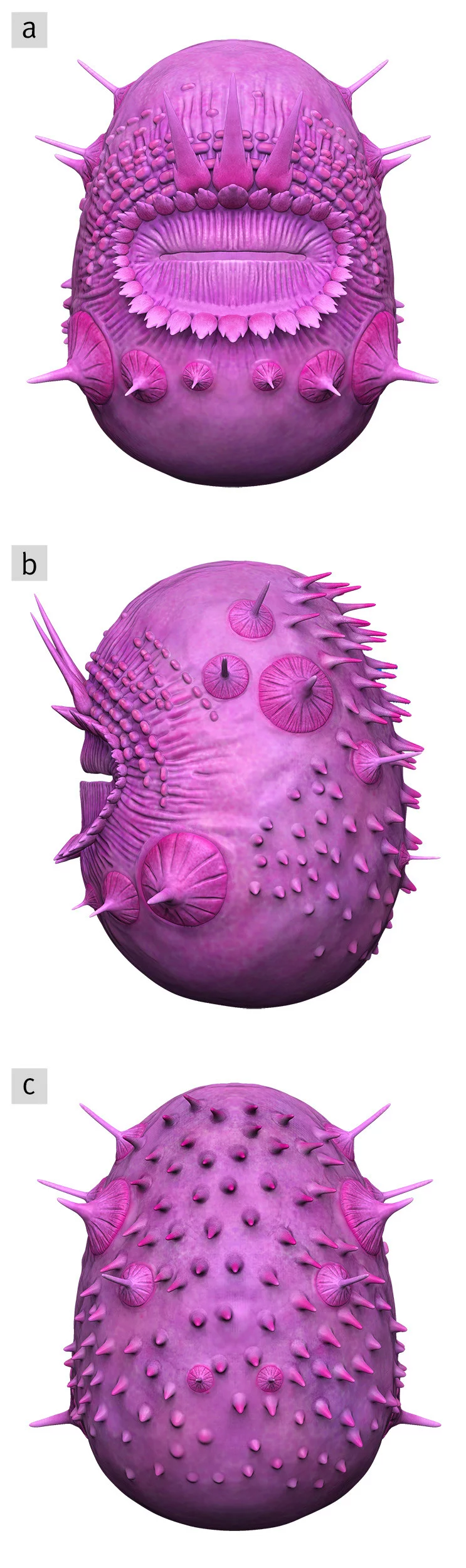

In 535 million year old rocks in China is a mysterious microfossil whose evolutionary affinity is hotly debated. Saccorhytus was originally described in 2017 as an ancestral deuterostome, a member of the group from which our own deep ancestors emerged. It is microscopic in size – about a millimetre in diameter – and resembles a spikey, wrinkly sack, with a mouth surrounded by spines and holes that were interpreted as pores for gills – a primitive feature of the group. This made for a very unexpected origin of deuterostomes: within sand-grain sized organisms that may have lived among the sand or floating in the sea. However, the evidence supporting this view was always very weak – were those holes around the mouth really gill pores?

The researchers tried to address this question by collecting new specimens of Saccorhytus, dissolving tonnes of rock with strong vinegar and picking through the resulting grains of sand for these rare fossils. The fossils are no longer rare – the teams recovered hundreds of specimens, many much better preserved than any seen before, providing new insights into the anatomy and evolutionary affinity of Saccorhytus.

"Some of the fossils are so perfectly preserved that they look almost alive," says Yunhuan Liu, professor in Palaeobiology at Chang’an University, Xi’an, China. "Saccorhytus was a curious beast, with a mouth but no anus, and rings of complex spines around its mouth."

X-rays reveal the secrets of the gill pores

The true story of Saccorhytus’ ancestry would lie in the microscopic internal and external features of this tiny fossil, and to reveal them the researchers turned to the X-rays of the Swiss Light Source SLS. At the TOMCAT beamline, the researchers were able to use a technique called X-ray tomographic microscopy. "This technique works like a medical CT scanner, but thanks to the very intense radiation of modern synchrotron facilities like the SLS, minute features less than a thousandth of a millimeter in size can be visualised in a short time," explains Federica Marone, beamline scientist at the TOMCAT beamline at the SLS.

By taking hundreds of X-ray images at slightly different angles, with the help of powerful computers, a detailed 3D digital model of the fossil could be reconstructed. "Synchrotron tomographic microscopy has become a key tool in paleontology and this work shows the amazing detail that can be preserved in the fossil record but also the power of X-ray microscopes in uncovering secrets preserved in stone without destroying precious and delicate fossils," says Marone.

When the global pandemic struck, the palaeontologists were unable to visit the synchrotron themselves. Thankfully, the analysis could still move forwards. "They sent us the specimens by post and we performed the tomographic scans at the TOMCAT beamline for them. Thanks to the long term collaboration of the teams involved, the paleontologists already had experience on how to best prepare and mount the material for the analysis and we knew the image quality required to extract the relevant information," Marone explains. "Saccorhytus is one of the weirdest fossils I’ve ever seen."

Striking Saccorhytus off the family tree

From the X-ray tomographic images, the paleaentologists had their answer: Saccorhytus was not a deuterostome, and has nothing to do with our evolutionary origin. There are no gill pores – the holes around the mouth turn out to be the bases of spines that broke away during the preservation of the fossils. Indeed, the digital models showed that pores around the mouth were closed by another body layer extending through, creating spines around the mouth. "We believe these would have helped Saccorhytus capture and process its prey," suggests Huaqiao Zhang from the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology.

But if Saccorhytus was not a deuterostome, then what was it? The researchers believe that Saccorhytus is in fact an ecdysoszoan: a group that contains arthropods and nematodes. "We considered lots of alternative groups that Saccorhytus might be related to, including the corals, anemones and jellyfish which also have a mouth but no anus," says Phil Donoghue, Professor of Palaeobiology at the the University of Bristol, who co-led the study. "To resolve the problem our computational analysis compared the anatomy of Saccorhytus with all other living groups of animals, concluding a relationship with the arthropods and their kin, the group to which insects, crabs and roundworms belong."

The mysterious case of the disappearing anus

Saccorhytus’ lack of anus is an intriguing feature of this microscopic, ancient organism. Although the question that springs to mind is the alternative route of digestive waste (out of the mouth, rather undesirably), this feature is important for a fundamental reason of evolutionary biology. How the anus arose – and sometimes subsequently disappeared – contributes to our understanding of how animal bodyplans evolved. Moving Saccorhytus from deuterostome to ecdysozoan means striking a disappearing anus off the deuterostome case history, and adding it to the ecdysozoan one.

"This is a really unexpected result because the arthropod group have a through-gut, extending from mouth to anus. Saccorhytus’s membership of the group indicates that it has regressed in evolutionary terms, dispensing with the anus its ancestors would have inherited," says Shuhai Xiao from Virgina Tech, USA, who co-led the study. "We still don’t know the precise position of Saccorhytus within the tree of life but it may reflect the ancestral condition from which all members of this diverse group evolved."

Text: Miriam Arrell and Phil Donoghue

Contact

Dr. Federica Marone

Beamline Scientist, X-ray tomographic microscop

Paul Scherrer Institute, Forschungsstrasse 111, 5232 Villigen PSI, Switzerland

Telephone: +41 56 310 53 18, e-mail: federica.marone@psi.ch

Prof. Philip Donoghue FRS

University of Bristol, School of Earth Sciences

Life Sciences Building, Tyndall Avenue, Bristol BS8 1TQ, UK

Telephone: +44 117 394 1209, e-mail: Phil.Donoghue@bristol.ac.uk

Original Publication

Saccorhytus is an early ecdysozoan and not the earliest deuterostome

Yunhuan Liu, Emily Carlisle, Huaqiao Zhang, Ben Yang, Michael Steiner, Tiequan Shao, Baichuan Duan, Federica Marone Welford, Shuhai Xiao, Philip C. J. Donoghue

Nature, 17 August 2022

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-05107-z

Copyright

PSI provides image and/or video material free of charge for media coverage of the content of the above text. Use of this material for other purposes is not permitted. This also includes the transfer of the image and video material into databases as well as sale by third parties.