John Millard is head of Technology Transfer at PSI. Intellectual property also falls within this area. In a conversation he tells how PSI protects its knowledge with patents and, thanks to its patents, further strengthens collaboration with industry and other research institutions.

Why does a research institution like PSI need patents at all?

If we have something patented, the aim is to get back additional value for our investments in research. In the simplest case, this can be licencing income, that is, additional financial resources gained through the marketing of the invention. These are then available to our researchers, their laboratory, and PSI and make our research even better. Besides this financial aspect, there are other important reasons why PSI patents innovations. A patent can be strategically important for PSI because it arouses the interest of industry and draws the attention of new potential industrial partners.

What motivates industrial companies to approach PSI?

If a research institute has applied for a patent, that speaks for its technical expertise. The companies are then interested either in whether they can obtain a licence for this patent or whether the patent is important for the further development of one of their existing products or technologies. When companies want to develop a new technology or look for new markets, they always analyse whether there is someone who is already working on the topic or has already registered patents. Such investigations can reveal what kind of research the competition is doing.

Are patents also useful in the academic sector?

It is similar to the situation in industry. If two academic partners want to collaborate to do research in a particular field and one of them has already patented something on the topic, this is a clear sign of their expertise and practical experience in the field. So a patent application makes us more attractive for a research collaboration. This is also important in national or international consortia if researchers from different institutions come together to address major scientific or social questions. Having a patent in hand improves our position there and makes PSI a sought-after partner.

Why is the confirmation of expertise by a patent so important?

Patents ensure that our knowledge can be better utilised. If researchers or companies want to newly develop or further develop something and in doing so would have to rely on protected technology, they need access to this patent. On the one hand, this offers the possibility that PSI can participate in others' projects. And on the other hand, a patent brings additional projects to PSI. With that, PSI gets something back from its investments. Not directly, from a licence, but rather because it opens the door for a new collaboration.

Could you provide specific examples of such collaboration?

We have a licencing agreement with the Swiss company Debiopharm for an active ingredient against a form of thyroid cancer. As a result, PSI receives licencing income. But it is equally important that a new, long-term collaboration has arisen here because the company wants to develop the active agent together with PSI. There are also other areas where companies have worked with PSI for a long time. Because they recognised that we not only have the patents, but we also have the know-how. The industry takes us seriously.

What effect does that have?

This type of cooperation is important to us because further research in one area remains here at PSI and yet is being done jointly with these companies. There are other companies that get in touch with us because we have specific know-how that would help them make progress. So we are automatically an important contact.

What know-how is that, specifically?

For some of our developments that we have patented, there is only a very small market. But they can be very important because they make things simpler or reduce costs. These, then, are technologies that we bring to the outside world in business or research. The monetary value of the patent may not be that high. But it leads to a boost for PSI's image. When a research institution is known and respected, new collaborations always arise. It's like a cycle: We invest money, resources, and know-how and gain prestige and new partners in return. This way we can keep improving.

We invest money, resources, and know-how and gain prestige and new partners in return.

How many patents does PSI currently have?

Currently there are just over a hundred patent families, that is, patents that trace back to one application. This includes patents on certain key PSI technologies, such as in the development of X-ray detectors and other measurement methods, in radiation therapy and diagnostics, in nuclear physics, and a few more areas.

How do you evaluate what a patent is worth?

What it's worth? To put it bluntly: by the model of car the inventor has bought. No, all joking aside – the financial value of a patent, unfortunately, only becomes clear in retrospect. Of course, before submitting a patent we check whether we see the potential, but a patent application always remains a highly speculative investment. In the end, just a small number of patents generate the lion's share of licencing income. Fortunately, a patent is useful to us in other ways.

Is there anything measurable about the value of patents, perhaps expressed in numbers?

What do you want to express in numbers? The number of products, jobs, sales? The potential added value due to a patent is very complex, because there are many factors involved that can't be measured. Naturally, you try to draw conclusions about the financial value of patents from the information available on patent applications, but this only yields a useful statement when it's averaged over many patents. The ETH Domain, to which PSI belongs, had a patent portfolio analysis done in 2018 to assess the quality of its patents. Here too, the patents were not assessed from a financial perspective.

How was the patent portfolio analysis carried out?

Among other things, they assessed how often a patent family was cited – an indication of its relevance – and in how many countries the patent was registered – a measure of its distribution. These two criteria tell a lot about whether a patent is valuable or not. Because they include, on the one hand, the self-assessment by the patent applicant, and on the other hand the external appraisal by the competition. International patent protection is pricey, and the more countries an inventor wants to protect his innovation in, the more expensive it gets. A comprehensive international patent application therefore signals that the inventor believes his patent is promising. Conversely, you can see how important a patent is when it is frequently cited by other researchers or companies as a reference for a technology.

Patents make it easier for PSI to transform our researchers' knowledge into commercial successes – for the benefit of industry, our research, and society.

For researchers, what makes it desirable to apply for patents?

Patents stand for innovation and bring appreciation. If a scientist wants to switch to industry, patents carry even more significance than scientific publications. Scientific publications are extremely important in the academic environment. From an industry perspective, though, patents are more valuable. If someone already has a patent, the people in the companies know that they are not only getting a new employee who knows a great deal in a certain area, but also one who can think commercially.

Does this commercial thinking also play a role at PSI?

Some researchers are already thinking entrepreneurially. They don't just come up with an invention that they want to patent. Often, they immediately have the idea of founding a spinoff too, so that they can further develop and market their invention. If a patent results in a spinoff, it is also a win for PSI. For example, we can set up a collaboration or licence the patent to the spinoff. We support spinoffs in every way possible. It's a win-win situation for both.

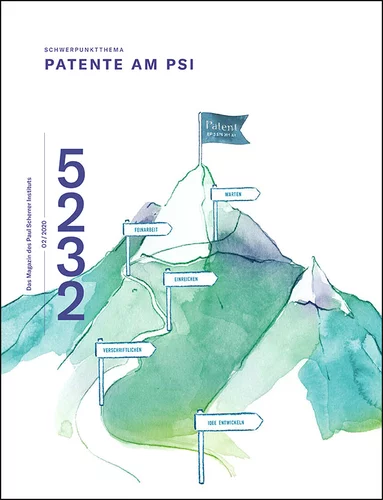

When does PSI consider filing a patent application?

At PSI we do a multi-stage assessment before filing. We only apply for a patent on an invention where we see added value for PSI. First of all, it's about justifying the effort that goes into a patent application. Including a possible total loss if the application is unsuccessful. And we clarify various technical questions in advance with a patent attorney or with the Swiss Federal Institute of Intellectual Property IPI in Bern. For example: How big is the inventive step? What is the state of the art in this technology? Could our patent be easily circumvented?

What is the most important step in a patent application?

Timing is important: The first one who gets there is the one who gets it. Once published, it can no longer be patented. So sometimes an unfinished dossier needs to be submitted in order to pre-empt a publication. It can also be a presentation or a manuscript prepared for a trade journal, perhaps with a brief description of what you want to patent. With this registration you are granted the priority date and twelve months to submit your application in full. That is, to fully formulate the idea and supplement it with sketches and data. After that, the inventor can publish results scientifically without hesitation, because the patent has already been registered.

What would happen if an idea was published without this registration?

As soon as an invention is published somewhere without prior registration, it is no longer patentable. All it takes is one page in a magazine. Companies have used this rule in the past to protect developments of their own that they did not want to patent due to the high patent fees, for example to prevent others from applying for a patent. It's different with us at PSI. When we apply for patents, it's not to protect ourselves. On the contrary, they serve to bring the outside world to us.

Interview: Sabine Goldhahn