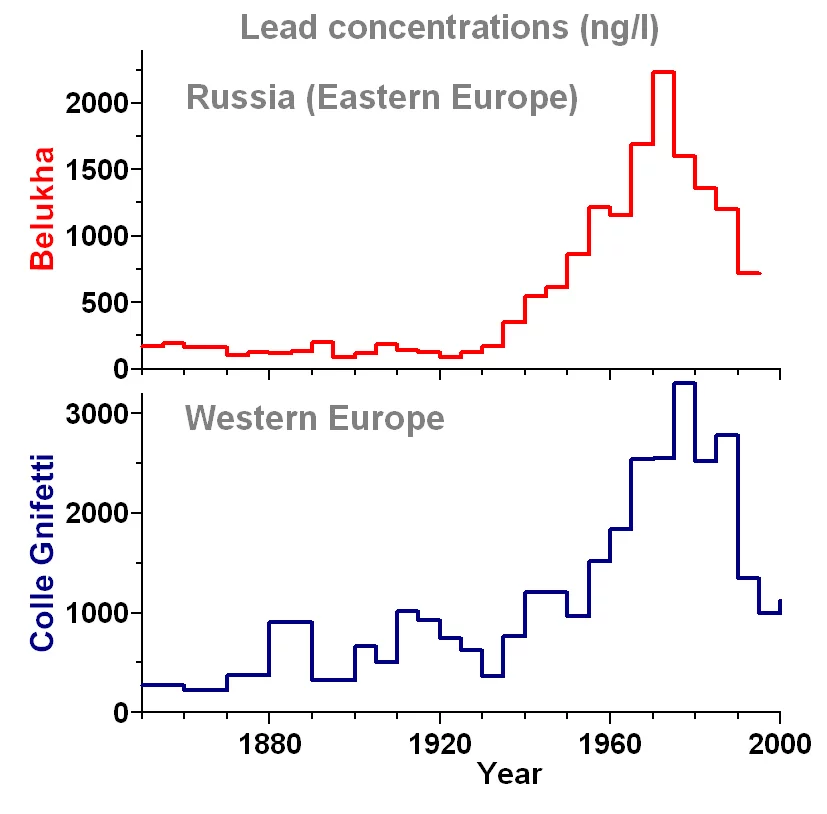

A research team from the Paul Scherrer Institute has reconstructed the concentration record of lead in the atmosphere in Russia since 1680. As no continuous atmospheric lead measurements had been made, the researchers are able to give the first outline of what the record could have been like. The results demonstrate a significant increase in the atmospheric lead concentrations since the 1930s and a significant reduction since the 1970s. The increase is interpreted as being due to rapid industrialisation and the enhanced use of leaded gasoline in automobiles. The reduction can be traced to economic difficulties and the associated dissolution of the former Soviet Union, accompanied by a decrease in exhaust emissions by road traffic. In an earlier research project, the researchers also found a similar reduction in Western Europe. Here, however, it was caused by the introduction of unleaded gasoline. The results in Russia were obtained by the research team from an ice core extracted from a glacier in the Altai Mountains. The composition of the atmosphere in the past is archived in the different ice layers. Lead concentrations and lead isotopic ratios in the ice core were measured with a sensitive (sector-field) mass spectrometer.

"Lead in the air is detrimental to health. Above all, it hinders the brain development of children", explains Margit Schwikowski, leader of the Analytical Chemistry research group at the Paul Scherrer Institute. The primary sources of lead in the atmosphere are lead compounds in leaded gasoline which are emitted into the air in exhaust gases. In order to reduce this lead pollution, the use of leaded gasoline in western countries was steadily reduced from the 1970s and ultimately prohibited. "From research that we published in 2004, we were able to show that the lead concentration since the introduction of unleaded gasoline in Western Europe has actually reduced significantly", stresses Schwikowski.

Russia and Western Europe — similar development, different reasons

"In our latest research, we determined the atmospheric lead concentrations in Russia since 1680, and observed a similar reduction in the period since the 1970s. We interpret this, however, as an unplanned effect that is associated with the decline of industry in the Soviet Union and the consequent decrease in exhaust emissions", explains Anja Eichler, a scientist in Schwikowski's research group, who carried out the studies.

The past conserved in ice

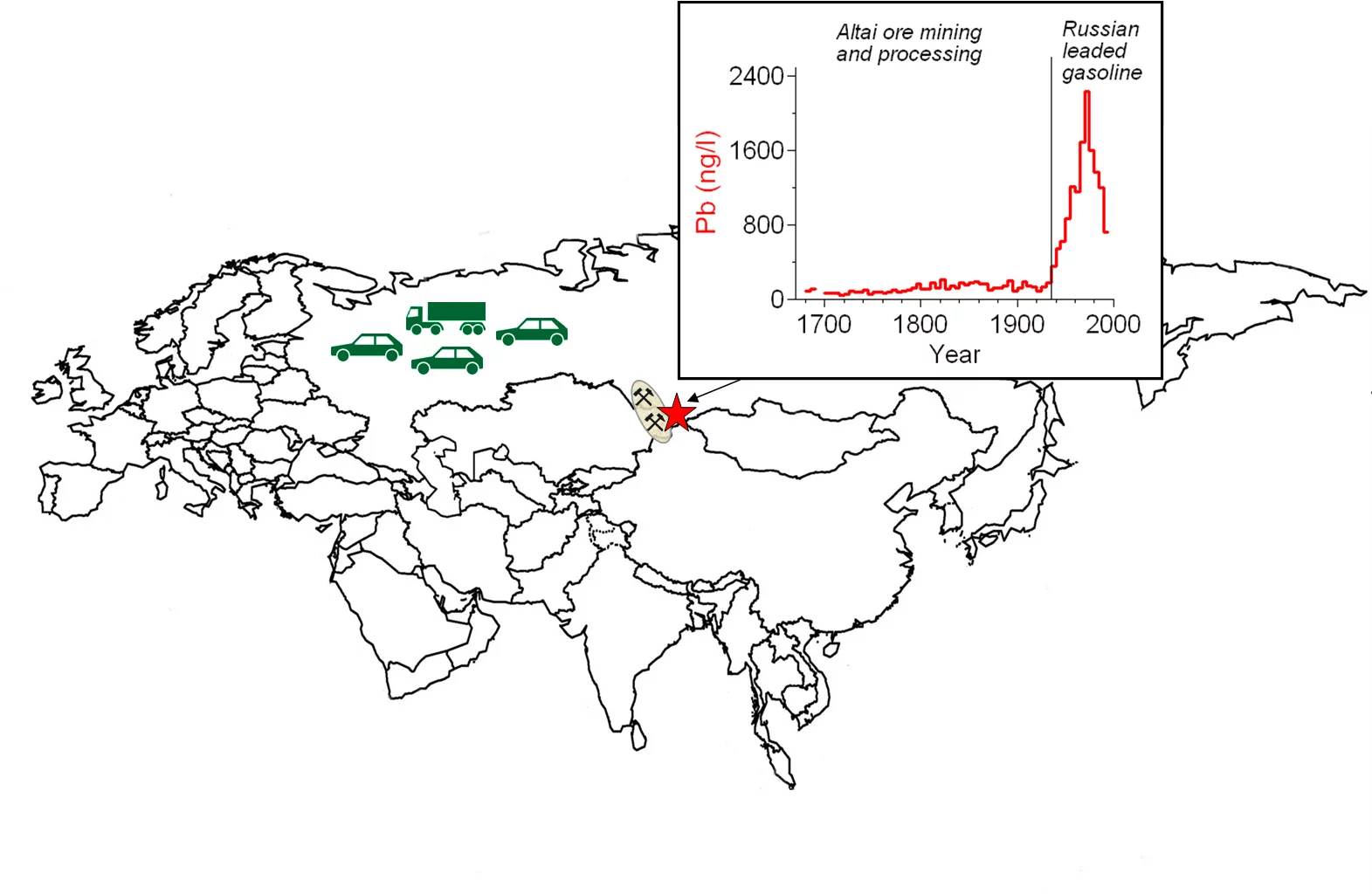

The researchers obtained the information about the lead concentrations in past centuries from an ice core which was drilled by an international research team under the leadership of Margit Schwikowski, in 2001, in the Russian Altai Mountains, in the border region of Russia with China, Mongolia, and Kazakhstan. The ice core was extracted from a glacier that has not melted during the last few hundred years. It was formed when snow fell year after year and was compressed under its own weight. As snow always contains traces of the different components of the atmosphere, the atmospheric composition of the past is thus preserved. Lead concentrations, as well as lead isotopic ratios, in the ice core were measured with a sensitive (sector-field) mass spectrometer.

Traces of silver mining and industrialisation

"Lead in the atmosphere has different sources", says Margit Schwikowski. "It can get into the atmosphere as mineral dust from deserts, or be released by volcanic eruptions. Most of it today, though, comes from human activity: from coal burning, from the mining and smelting of metals, and from leaded gasoline." These various sources can also be detected in the lead from Russia. "Until the eighteenth century, we only see lead from natural sources. Since about 1770 there is a rise, because silver for the production of Russian coins had started to be mined in the neighbourhood of the glacier", explains Anja Eichler. "Since the time of Catherine the Great, all Russian coinage was produced in the Altai Mountains. From the 1930s, lead (Pb) concentrations increased strongly, caused by the progressive industrialisation of the Soviet Union and the associated heavy usage of leaded gasoline." Here, the results from the measurements in Russia differ significantly from those in Western Europe, where the increase of lead concentrations associated with industrialisation could already be seen at the end of the nineteenth century. As no continuous measurements of the atmospheric lead content were ever taken, these results by PSI scientists give a first comprehensive overview of its development — in the current work on Russia and in the publication of 2004 for Western Europe.

How lead from different sources can be distinguished

"We determine not only the amount of lead but can also, to some extent, investigate the contribution of different lead sources from the lead isotopic ratios. In nature, three isotopes above all occur, which are found in different ores in varying proportions", says Eichler. "In this way, we can show that no lead appears in Russia from leaded gasoline used in Europe. This lead came from Australian ores and has a completely different composition to the Russian one, which means that the introduction of unleaded gasoline in Europe had no influence on the lead concentration in Russia. We can also determine when the lead began to originate mostly from Altai ores and not from mineral dust. However, the lead from silver mining cannot be distinguished by our method from the lead used in gasoline, because both come from the same deposit."

About PSI

The Paul Scherrer Institute develops, builds and operates large, complex research facilities, and makes them available to the national and international research community. The Institute's own key research priorities are in the investigation of matter and material, energy and the environment; and human health. PSI is Switzerland's largest research institution, with 1500 members of staff and an annual budget of approximately 300 million CHF.

Contact

Prof. Dr. Margit Schwikowski, Laboratory of Radiochemistry and Environmental Chemistry, Paul Scherrer Institute, CH-5232 Villigen PSIE-mail: margit.schwikowski@psi.ch, Phone: +41 56 310 41 10

Dr. Anja Eichler, Laboratory of Radiochemistry and Environmental Chemistry, Paul Scherrer Institute, CH-5232 Villigen PSI

E-mail: anja.eichler@psi.ch, Phone: +41 56 310 20 77

Original Publication

Three Centuries of Eastern European and Altai Lead Emissions Recorded in a Belukha Ice CoreA Eichler, L Tobler, S Eyrikh, G Gramlich, N Malygina, T Papina, M Schwikowski,

Environmental Science & Technology, Vol. 46, No. 8, pp. 4323 – 4330 (2012).

DOI: 10.1021/es2039954