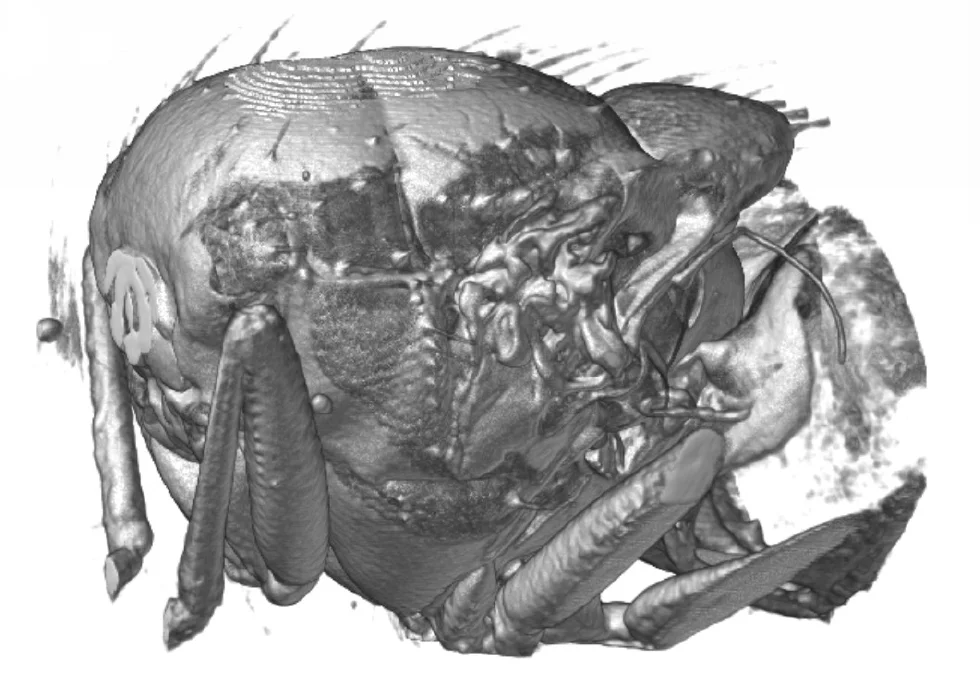

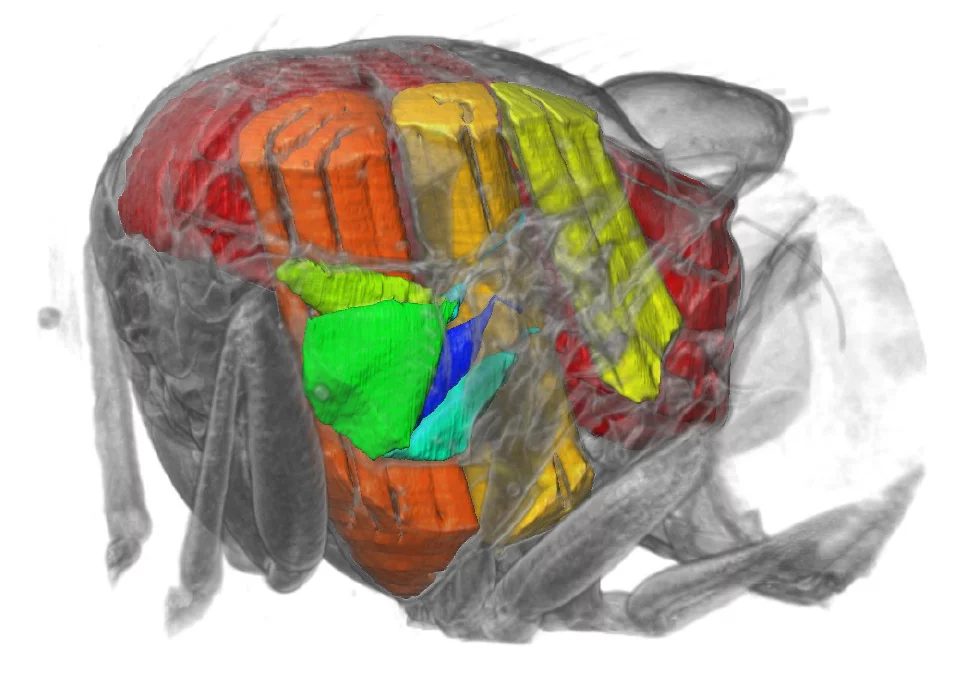

Scientists have used a particle accelerator to obtain high-speed 3D X-ray visualizations of the flight muscles of flies. The team from Oxford University, Imperial College, and the Paul Scherrer Institute (PSI) developed a groundbreaking new CT scanning technique at the PSI’s Swiss Light Source to allow them to film inside live flying insects. Their article, including 3D movies of the blowfly flight motor, is published March 25 in the open access journal PLOS Biology. The movies offer a glimpse into the inner workings of one of nature’s most complex mechanisms, showing that structural deformations are the key to understanding how a fly controls its wingbeat.

In the time that it takes a human to blink, a blowfly can beat its wings 50 times, controlling each wingbeat using numerous tiny steering muscles – some as thin as a human hair. The membranous wings contain no muscles, so all of the flight muscles are hidden out of sight within the thorax. “The thoracic tissues block visible light, but can be penetrated by X-rays”, says Rajmund Mokso, the scientist in charge of the experiment at PSI. “By spinning the flies around in the dedicated fast-imaging experimental setup at the Swiss Light Source, we recorded radiographs at such a high speed that the flight muscles could be viewed from multiple angles at all phases of the wingbeat. We combined these images into 3D visualizations of the flight muscles as they oscillated back and forth 150 times per second.”

“This experiment is a milestone in tomographic microscopy using X-rays. It shows details of the fly's muscles on the scale of a few thousandths of a millimeter and allows us to follow their motion with unprecedented time resolution", says Marco Stampanoni, head of the X-Ray Tomography Group at PSI and professor at ETH Zurich. "This work is the result of a longterm development performed by PSI scientists and places the SLS at the forefront in tomographic imaging.”

The flies responded to being spun around by trying to turn in the opposite direction, allowing the scientists to record the asymmetric muscle movements associated with turning flight. “The steering muscles make up less than 3% of a fly’s total flight muscle mass”, says Prof. Graham Taylor who led the study in Oxford, “so a key question has been how the steering muscles can modulate the output of the much larger power muscles. The power muscles operate symmetrically, but by shifting each wing’s mechanism between different modes of oscillation, the fly can divert power into a steering muscle specialized to absorb mechanical energy – rather like using the gears of a car for braking.”

The scientists hope to use their results to inform the design of new micromechanical devices. “Flies have solved a problem faced by engineers working on the same scale” says Prof. Taylor: “How to produce large, complex, three-dimensional motions, using actuators that only generate small, simple, one-dimensional ones?” The clever design of the blowfly flight motor solves that problem admirably, as the results of this study show. Dr. Simon Walker from Oxford, who was joint first author of the study with Daniel Schwyn, adds: “The fly’s wing hinge is probably the most complex joint in nature, and is the product of more than 300 million years of evolutionary refinement. The result is a mechanism that differs dramatically from conventional manmade designs; built to bend and flex rather than to run like clockwork.”

The 3D movies

Text based on a press release published by the University of Oxford

About PSI

The Paul Scherrer Institute PSI develops, builds and operates large, complex research facilities and makes them available to the national and international research community. The institute's own key research priorities are in the fields of matter and materials, energy and environment and human health. PSI is committed to the training of future generations. Therefore about one quarter of our staff are apprentices, post-graduates or post-docs. Altogether PSI employs 1900 people, thus being the largest research institute in Switzerland. The annual budget amounts to approximately CHF 350 million.

Contact

Prof. Graham Taylor is Associate Professor of Mathematical Biology in the Department of Zoology, University of Oxford. tel. +44 1865 271219; graham.taylor@zoo.ox.ac.ukDr. Simon Walker is a Royal Society University Research Fellow in the Department of Zoology, University of Oxford. tel. +44 1865 271223; simon.walker@zoo.ox.ac.uk

For information on imaging technology contact technical lead Dr. Rajmund Mokso, Beamline Scientist, Paul Scherrer Institute. tel. +41 56 310 5628; rajmund.mokso@psi.ch

For information on insect sensory motor control, contact neurobiology lead Dr. Holger Krapp, Reader in Systems Neuroscience, Department of Bioengineering, Imperial College London, tel. +44 20 7594 2014; h.g.krapp@imperial.ac.uk

Original Publication

Walker, SM, Schwyn, DA, Mokso, R, Wicklein, M, Müller, T, Doube, M, Stampanoni, M, Krapp, HG, Taylor, GKIn vivo time-resolved microtomography reveals the mechanics of the blowfly flight motor.

PLoS Biol 12(3): e1001823 (2014). doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001823