In 1984, people were irradiated at the Paul Scherrer Institute PSI for the first time against a rare but very malignant type of cancer: They had a tumour in their eye. The treatment – at the time the first of its kind in Western Europe – was a complete success. Since then, researchers at PSI and the Jules-Gonin Eye Hospital in Lausanne have continued to improve the technique. Not only do protons save the lives of those affected, in most cases they also save their eyesight.

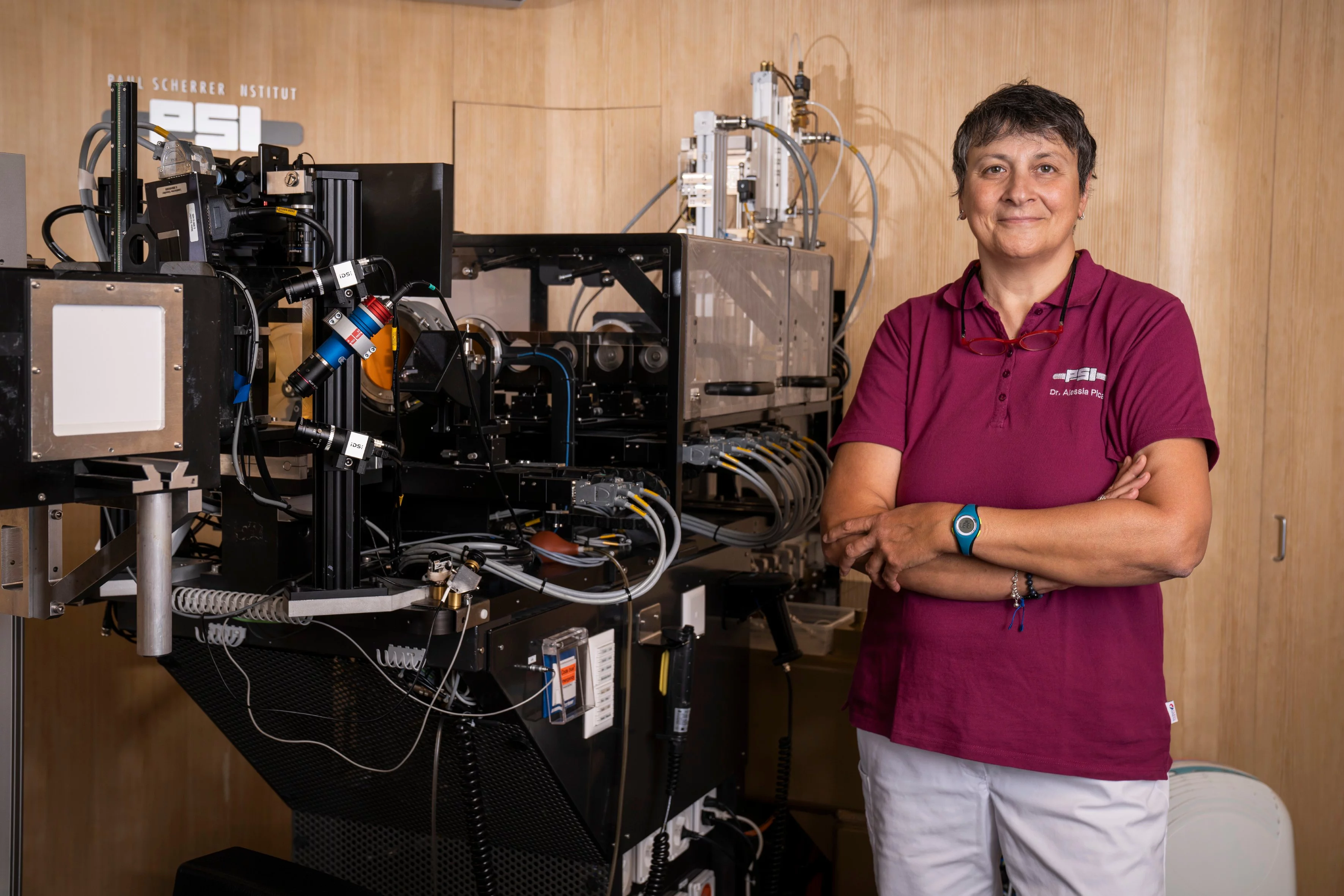

“Finding out that you have cancer is already bad enough, but a tumour in the eye hits most patients particularly hard,” says radiation oncologist Alessia Pica, who is responsible for eye treatments at the Center for Proton Therapy at PSI. “For many, the eye is a link to the soul and the most important way to be in contact with other people. The prospect of possibly losing an eye is a tragedy for those affected.”

At PSI, Alessia Pica treats people with a very rare type of cancer: eye cancer. In Switzerland, around 60 people suffer from it each year. The term eye cancer (or ocular cancer) covers several types of tumours; one of them is the uveal melanoma, a tumour that arises from the pigment cells which give colour to the eye.

Once diagnosed, this type of cancer requires particularly quick action. That’s because the tumours are usually ticking time bombs: In many cases, metastases form, which without treatment often lead to death within a few months. “These are very aggressive tumours,” says Alessia Pica. Her patients also include young people between 16 and 39 years of age: “This is not a cancer that occurs only with old age.”

How it all began

Before the 1980s, there was essentially only one option for eye tumours: The eyeball was removed in a surgical operation. But then researchers at the Center for Proton Therapy at PSI, together with the Jules-Gonin Eye Hospital in Lausanne, established an alternative therapy: The tumour, which often is less than a centimeter in thickness, is irradiated in a very targeted way with protons, positively charged particles. “We make an effort not only to render the tumour harmless, but also at the same time to save the eye and, if possible, preserve vision,” says Damien Weber, Head and Chief Physician of the Center for Proton Therapy.

In 1975, doctors in Boston irradiated an eye tumour with protons for the first time – successfully. With this type of irradiation, it is possible to control the penetration depth very precisely, so that the protons release most of their energy in the tumour – thus healthy tissue behind the tumour is protected. This is a big advantage, particularly for tumours in the eye, a very sensitive organ.

Less than a decade later, the new treatment method was established in Switzerland by two pioneers: Charles Perret, a physicist at PSI, and Leonidas Zografos, an ocular oncologist at the Jules-Gonin Eye Hospital in Lausanne. Together they adapted the procedure tested in Boston and developed it further. OPTIS was created: a facility at PSI that can be used to irradiate eye tumours in a targeted manner with great precision. One of the first patients in March 1984 was a photographer from the French-language Swiss newspaper La Tribune-le Matin, who together with a colleague published an article about the new treatment method.

Further improved

The irradiation facility where the first patients were treated at PSI no longer exists. In the early 2000s, the Center for Proton Therapy obtained a new particle accelerator and, with it, a completely new treatment facility for eye tumours: OPTIS2 went into operation in 2010. “Thanks to its unique design, OPTIS2, together with the gantries, treatment facilities where other types of cancers are irradiated, could be directly connected to the high-energy cyclotron,” says medical physicist Jan Hrbacek, group head of OPTIS. “We can now position the patient so precisely in the treatment chair that there is less than 0.3 millimetre deviation from the position planned in the treatment software.” This is important so that the proton beam precisely hits the tumour – nothing more and nothing less.

The irradiation procedure itself has remained the same to this day. To make the tumour visible with X-ray, the patient first undergoes surgery under general anaesthesia at the eye hospital: tiny metal plates are sewn onto the outer covering of the eyeball, surrounding the tumour. This allows to localize the tumour in an X-ray image. Proton therapy is then realised at PSI on four consecutive days of a week. The irradiation itself only takes one minute per session. “We irradiate the tumour with high dose of radiation, because melanomas are very resistant to radiation,” Damien Weber explains.

In treating an eye tumour, there’s no time to lose, says Alessia Pica. This is necessary because the risk that metastases will form is significant. “As soon as the diagnosis is established, an appointment will be made for the metal clips operation. Usually in the following week, irradiation takes place. Many patients don’t even have time to realise that they have cancer.”

Cooperation as the key to success

The eye is a delicate and complex organ, and the treatment of eye tumours is therefore a complicated undertaking. Irradiation at PSI is not the end of the story. During the years after proton therapy, follow-up is organized at the Jules-Gonin Eye Hospital in Lausanne. There, a former collaborator of Leonidas Zografos has taken over as his successor and Head of the adult Ocular Oncology Unit: Ann Schalenbourg.

“In the beginning, proton therapy of the eye had a bad reputation,” Ann Schalenbourg recalls. “Certain colleagues said that the irradiation caused so many side-effects that eventually the eye would have to be removed anyway. But Leonidas Zografos firmly believed in the technique.” He continuously improved both the treatment and the follow-up and was ultimately proven right: the eye tumour can be eradicated with proton therapy; at the same time, with the appropriate follow-up care, the eye can be saved. Patients now receive, among other things, prophylactic medication – specifically, monoclonal antibodies such as bevacizumab, ranibizumab, or aflibercept – injected into the irradiated eye. These drugs prevent the formation of new blood vessels and thus prevent bleeding and other complications.

“It is inspiring to work with a clinic that is so specialised in treating eyes,” says Damien Weber. “The Jules-Gonin Eye Hospital is the only one of its kind in Switzerland.” In addition, PSI works closely with the eye clinic at the University Hospital of Zurich, as well as with the University Clinic for Ophthalmology and Optometry in Innsbruck.

Successes

The success rate for proton therapy at PSI is unbeatable worldwide: in 98 percent of cases, the tumour in the irradiated area can be eradicated completely and does not grow back. Thanks to intensive research at the Jules-Gonin Eye Hospital, the follow-up has been optimised so that more than 90 percent of those treated keep their eyes – the previously standard procedure of removing the eye is no longer necessary. And even more than 60 percent of patients retain useful vision.

To date, more than 8,000 eye cancer patients have been irradiated at PSI. “This is more than at any other therapy centre worldwide,” says Jan Hrbacek. Alessia Pica adds: “I hope that in the future there will continue to be people who dedicate themselves entirely to treating this type of tumour. It’s not something you can do on the side. You have to know the tumour really well to be successful.”

Text: Brigitte Osterath

© PSI provides image and/or video material free of charge for media coverage of the content of the above text. Use of this material for other purposes is not permitted. This also includes the transfer of the image and video material into databases as well as sale by third parties.

Contact

Further information

About PSI

The Paul Scherrer Institute PSI develops, builds and operates large, complex research facilities and makes them available to the national and international research community. The institute's own key research priorities are in the fields of future technologies, energy and climate, health innovation and fundamentals of nature. PSI is committed to the training of future generations. Therefore about one quarter of our staff are post-docs, post-graduates or apprentices. Altogether PSI employs 2200 people, thus being the largest research institute in Switzerland. The annual budget amounts to approximately CHF 420 million. PSI is part of the ETH Domain, with the other members being the two Swiss Federal Institutes of Technology, ETH Zurich and EPFL Lausanne, as well as Eawag (Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology), Empa (Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology) and WSL (Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research). (Last updated in June 2023)