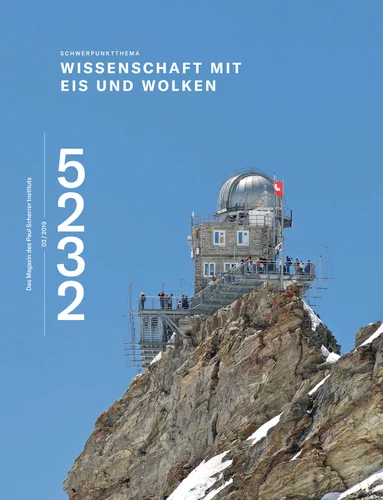

At Jungfraujoch, PSI scientists are studying airborne particulate matter. And have to deal with the fact that the human body is not made for life 3,500 metres above sea level.

On the last nine kilometres the railway climbs steeply up the mountain through a rock tunnel, the passengers get light-headed. The sinking air pressure makes the temples throb. Martin Gysel smiles. "Even people who are not coming up for the first time often feel sick here."

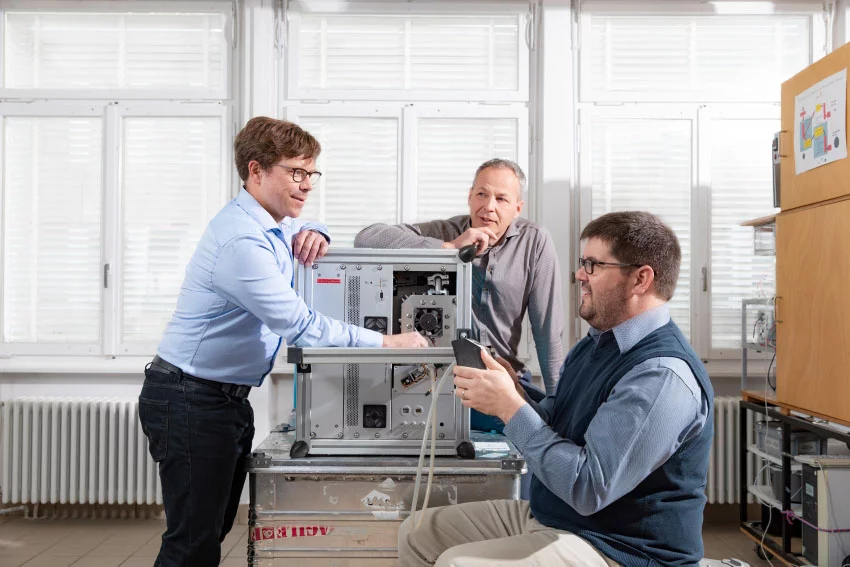

Fortunately, this is the final spurt to the Jungfraujoch, situated around 3,500 metres high between Mönch and Jungfrau in the Bernese Alps. Next to Gysel, head of the research group for aerosol physics at the Paul Scherrer Institute, sit technician Günther Wehrle and environmental engineer Benjamin Brem. Apart from them, there are alsoa lot of tourists riding the Jungfrau Railway: Around a million people visit the Jungfraujoch every year.

Finally, with a small jolt, the cars come to a halt. They have reached Europe's highest railway station. The tourists alight and stream to the viewing platform or into the Ice Palace: a walkway of passages and halls carved into the glacier ice.

Gysel, Wehrle, and Brem on the other hand grab their backpacks and go to an inconspicuous lattice door. Behind it begins an area that's not open to the public: the high alpine Jungfraujoch research station, which went into operation in 1931, around 20 years after the opening of the Jungfrau Railway. Benjamin Brem, a new member of Martin Gysel's research group, is here for the first time today. He will get to know this most remote outpost of PSI, because from now on he will be responsible for the central project in Gysel's group on Jungfraujoch: the long-term series of measurements on aerosol particles.

Aerosols, better known as particulates, are another factor in human-made climate change along with CO2 and methane. But while those two gases basically lead to warming of the climate, the influences of aerosols are more complex and to some extent even have the opposite effect. "The greatest uncertainty in climate predictions is due to the manifold properties of the aerosols. For that reason, a lot of research is still needed here", says Gysel.

First, the three researchers go to the station's living quarters. Scientists from all over Europe often stay here overnight, together with the engine drivers of the Jungfrau Railway – up to 13 people can be accommodated at the same time. The station's research lab, which is operated by an international foundation, is housed in the Sphinx Observatory, the building situated highest on the Jungfraujoch, which with its dome and observation deck is the emblem of the mountain station. Researchers from Empa and the University of Bern also conduct research here. The PSI collaborate with them scientifically on a regular basis.

In the engine room

The path from the living quarters to the Sphinx leads through the middle of tourist territory. Once Gysel is past this and opens another lattice door, a curious visitor with an outstretched selfie stick wants to go inside too. "Sorry, only for scientists", Gysel says. An elevator takes the trio of researchers up to the top of the Sphinx. While one level below them tourists are taking pictures of the alpine panorama and buying T-shirts or expensive watches, the three researchers get down to work.

"Take off your jackets", technician Wehrle recommends. Despite the sub-zero temperatures outside the windows, here in the research area it feels like an engine room: Dozens of measuring instruments and computers are humming to themselves, and it's hot and loud. So the three talk only when necessary while they check devices and recalibrate some of them.

When in doubt, call PSI. Down there they have more oxygen in the brain.

The human body is not designed for work at 3,500 metres above sea level. Just climbing the stairs is exhausting. Concentration rapidly fades. Many know the story of an overnight guest at the station who wanted to cook spaghetti one evening. Only when everyone was seated at the table, hungry for supper, did he realise he had only boiled water. And Wehrle knows from his own experience: "Sometimes you brood for half an hour over a problem that would normally be solved in a minute", the technician says.

"Do you have any tips on how to prevent this?", asks Brem, who until recently worked at an altitude of 440 metres, at the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology Empa in Dübendorf. Wehrle shrugs his shoulders: "Do one thing after another", he advises. "And when in doubt, call PSI. Down there they have more oxygen in the brain."

Doing research in the troposphere

While his two colleagues calibrate a measuring device, Gysel produces a palette with small filters the atmospheric researchers use to collect aerosols. The filter from Jungfraujoch is light beige, the one from the city pitch black. "The concentration of soot particles is sometimes a thousand times greater in a city", Gysel says.

Thanks to its height, the Jungfraujoch is a very good place to study how short-lived particles change on their way from Earth's surface to the higher layers of the atmosphere, where they eventually influence cloud formation. Benjamin Brem has therefore taken on a task with a lot of responsibility: The PSI measurement series on aerosol particles has been running for more than 20 years in conjunction with 30 other measurement stations worldwide. "With this we get unique large-area insights into the processes in the atmosphere and can provide a better basis for climate research", Gysel says.

But increasingly, the researchers are spared longer stays in the thin air at the research station. Thanks to automation, the measuring instruments can for the most part be monitored from PSI in Villigen; small disruptions can be resolved by the operations manager on-site. The PSI researchers only make the trip for more complex work, for example to set up the instruments for a specific research question.

Shortly after nine o'clock in the evening of their first day on the Jungfraujoch, Brem and Wehrle finally head back down to the living quarters. There Martin Gysel is already sitting at his laptop, writing the maintenance report.

Benjamin Brem has coped better with the thin air than many others before him. "Only this here", he laughs as he taps on the pen in the breast pocket of his checked shirt – "I've been looking for all day."

Text: Joel Bedetti