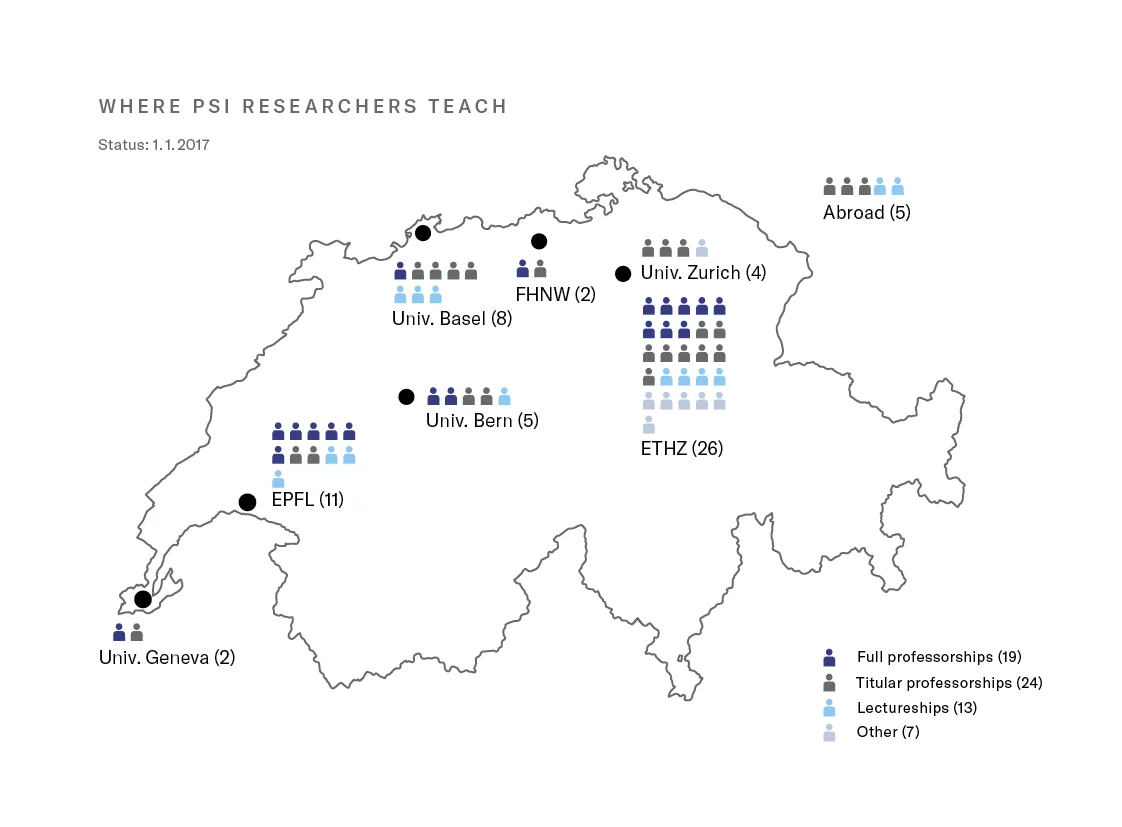

They have two e-mail addresses, two offices, and two filing cabinets in two locations: Around 60 of the researchers at PSI are at the same time professors or lecturers at a Swiss university. Even if their scheduling is sometimes tricky, in the end, PSI and the universities both profit from these researchers with double affiliations.

Frédéric Vogel sighs a bit theatrically: Any time I need a particular textbook in a hurry, it's guaranteed to be in my other office.

Vogel is a researcher at PSI. In addition, he is a professor at the University of Applied Sciences and Arts Northwestern Switzerland FHNW in Brugg/Windisch. In one location he explores how biomethane for energy generation can be produced from algae, liquid manure, and sewage sludge. At the other, he gives lectures about processing technology and renewable energy sources. His work contract allocates his time roughly half-and-half between the two jobs.

Human connections

Vogel is not alone: Around 60 of the nearly 800 researchers who work at PSI have such joint appointments with Swiss universities or universities of applied sciences. Through their double status, they weave a fine spider web between PSI and the universities. Its filaments have a total length of more than 700 kilometres. The connections are invisible and run mostly along the railway lines, sometimes along the roads. They are also strong and resilient: The close collaboration that comes about when one and the same person feels professionally at home in two places can hardly be achieved by other means.

Vogel and the other double agents know this. We bring the research topics of PSI to the universities and we let people know what possibilities the big machines here can offer

, Vogel explains. The unique large-scale research facilities of PSI are generally available to scientists from all kinds of research institutions, in particular the Swiss universities.

Naturally, the connection also operates in the other direction: As academics, we open doors for students

, says Laura Heyderman, a full professor at ETH Zurich and, at the same time, a researcher at PSI. Through my lectures, I get to know students and then some of them come to PSI — for an internship, for a final thesis project, or as young scientists.

Heyderman's research group at PSI is always on the lookout for engaged, inventive young talents who can think on a very small scale as well as the large scale: Here Heyderman and her collaborators are investigating the behaviour of tiny nanomagnets that might one day become the basis for novel computing technology. Their sophisticated experiments often take place at the Swiss Light Source SLS, one of the large-scale research facilities of PSI.

Rail connections

In the daily grind, the joint professorship also has its dark side: The office work comes in double rations: meetings, e-mails, administrative tasks

, Heyderman admits. Still, she basically enjoys the nomadic life, as she calls her work at — and between — the two institutions. I always have the documents I need to work on in my backpack.The train is, so to speak, my third office.

Switzerland's railway network is my ally

, says Christian Rüegg, head of the Laboratory for Neutron Scattering and Imaging. He is one of two PSI researchers who travel all the way to the University of Geneva where he has a titular professorship. He lives in Aarau which is between the two work locations. Nevertheless, it takes him three hours to get to Geneva. It's quite clear that I have to organise myself accordingly

, he says. So he doesn't hold his lectures in Geneva on a weekly basis, but rather once or twice per semester in single blocks.

That fits well with his research at PSI, which also takes place in blocks: In his office there is a schedule on the wall where he can see which weeks of the year he and his co-workers can have measurement time at SINQ, the large neutron source of PSI. Rüegg needs the neutron beam for his experiments on magnetic materials. PSI is famous for these large-scale research facilities. It's first-class and unique: Not only do you have these facilities and the associated infrastructure, but at PSI you also find all the experts needed to build them and ensure their perfect operation. The individual Swiss universities could not provide that — and thanks to PSI, they don't need to.

Conversely, the respective universities also have hidden talents: Universities of applied sciences, for example, are very good at building up partnerships with industrial firms. This skill is something I can also profit from at PSI

, Vogel says. He and the other PSI researchers with double status find that the many advantages more than compensate for the everyday hurdles so they keep on weaving the fine, resilient network that few may know about but many use.

Text: Paul Scherrer Institute/Laura Hennemann