At CERN, the European Organisation for Nuclear Research in Geneva, an international research team led by the Paul Scherrer Institute PSI has conducted especially precise measurements of atmospheric chemistry. Through this study the researchers were able to show how harmful particulate matter arises from vehicular emissions and biomass combustion. Their findings are helping to make existing models of particle formation more accurate.

Anthropogenic organic aerosols are carbon-containing particles emitted by humans into the air, which are classified as particulate matter. They pose a significant health threat and contribute to millions of deaths worldwide each year. Especially in large cities, incomplete combustion processes from transportation, industry, and households produce exhaust gases that form harmful, respirable particles.

In an international study at CERN, the European Organisation for Nuclear Research in Geneva, researchers led by PSI have gained new insights into the formation of these organic aerosols. Their results show that such pollutants often form only after several oxidation steps. This suggests that pollution with anthropogenic particulate matter has a greater regional impact than previously assumed. This in turn suggests that it is not enough to simply reduce direct emissions from factories, homes, and vehicles, for example, with particulate matter filters. Rather, the precursor gases from which harmful organic aerosols later form must also be controlled. The researchers report their findings in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Human-made particulate matter forms more slowly

Researchers previously assumed that organic aerosols form through a single oxidation step. Natural precursor gases such as terpenes and isoprene – hydrocarbons emitted by plants – quickly add oxygen and thus directly form solid airborne particles.

However, the new study reveals that anthropogenic emissions behave differently. The precursor gases—such as toluene and benzene from automobile exhaust and organic material combustion—undergo multiple oxidation steps before forming solid particles. “This finding challenges the previous assumption that pollutants form primarily near the emission sources,” says Imad El Haddad, project leader of the new study. “It shows instead that anthropogenic aerosols undergo a longer formation process whereby their impacts extend regionally.”

A unique simulation chamber

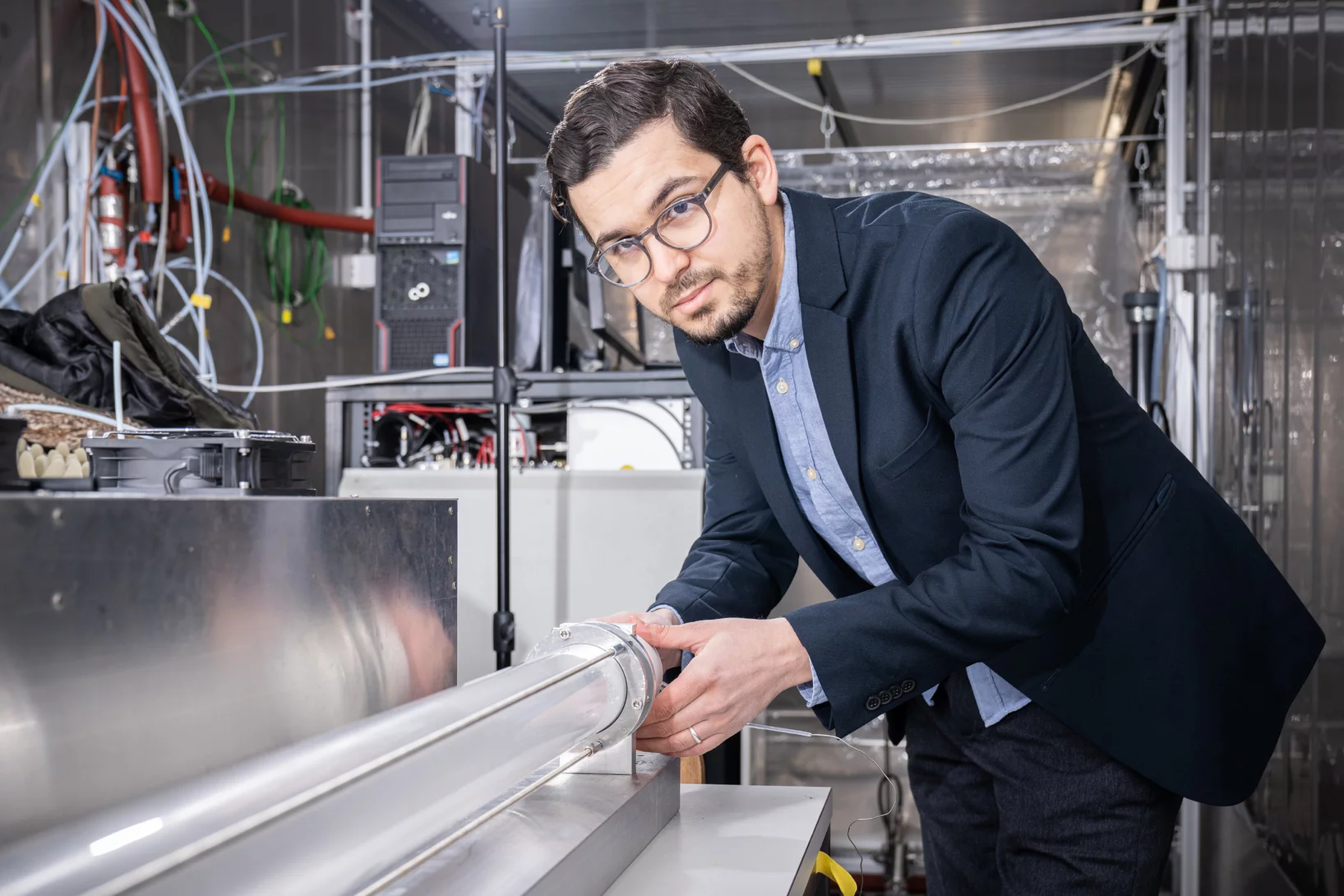

The new study was conducted at CERN's CLOUD (Cosmics Leaving Outdoor Droplets) simulation chamber. More than 70 researchers from Europe and North America collaborated to simulate urban air pollution and track the formation of organic aerosols. The CLOUD facility is the cleanest atmospheric simulation chamber in the world and enables researchers to control parameters such as temperature and pressure with extreme precision – the temperature to approximately one-tenth of a degree. Its stainless steel cylinder has a capacity of approximately 26 cubic metres. High-precision sensors ensure that changes inside the cylinder can be observed down to the second. For their experiments, the researchers filled the chamber with a gas mixture resembling urban smog to trace the transformation of exhaust gases into organic aerosols.

Working in shifts, the researchers continuously measured the simulated urban smog. They determined the size distribution of the forming particles using a technique known as mobility analysis and determined the molecular identity of the condensing vapours in real time using mass spectrometry. They also precisely tracked what proportions of precursor gases and their products condensed on the chamber walls. This must be taken into account in calculations for pollutant formation. “Thanks to the precise observations, we are now better able to understand how anthropogenic aerosols form and grow in the air,” says El Haddad.

More precise predictions

The bottom line of the study is that a significant proportion of anthropogenic organic aerosols forms not after the initial oxidation, but only after additional oxidation steps that can take between six hours and two days. The research team estimates that this multi-step oxidation accounts for more than 70 percent of the total anthropogenic organic aerosol pollution.

Their results can improve air pollution models by enabling more accurate predictions of particulate matter concentrations, providing a better understanding of regional impacts. They also underscore the importance of controlling not only the direct emission of particulate matter, for example, through particle filters, but also the emission of precursor gases that later form solid particles. This could help to combat air pollution more effectively and thus improve public health.

Contact

Original publication

-

Xiao M, Wang M, Mentler B, Garmash O, Lamkaddam H, Molteni U, et al.

Anthropogenic organic aerosol in Europe produced mainly through second-generation oxidation

Nature Geoscience. 2025; 18(3): 239-245. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-025-01645-z

DORA PSI

More articles on this topic

About PSI

The Paul Scherrer Institute PSI develops, builds and operates large, complex research facilities and makes them available to the national and international research community. The institute's own key research priorities are in the fields of future technologies, energy and climate, health innovation and fundamentals of nature. PSI is committed to the training of future generations. Therefore about one quarter of our staff are post-docs, post-graduates or apprentices. Altogether PSI employs 2300 people, thus being the largest research institute in Switzerland. The annual budget amounts to approximately CHF 460 million. PSI is part of the ETH Domain, with the other members being the two Swiss Federal Institutes of Technology, ETH Zurich and EPFL Lausanne, as well as Eawag (Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology), Empa (Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology) and WSL (Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research). (Last updated in June 2024)