Interview with Thomas Huthwelker

The Paul Scherrer Institut spares no effort in providing scientists from all over the world with the infrastructure they need to acquire new knowledge. Engineers, technicians and scientists from a range of disciplines work hand in hand. Physicist Thomas Huthwelker has dedicated himself to this task. An interview with him was published in the latest issue of the PSI magazine Fenster zur Forschung.

Dr. Huthwelker, the facilities at the Paul Scherrer Institute are only used by PSI-Scientists for a small proportion of the time; they are actually open to research groups from around the world.

Facilities like the ones we have can only be operated at an enormous expense, so there are only a few of them around the world. Nevertheless, to give all researchers access, we have to make time available for them at our facilities. Whoever arrives here will already have been through a highly elaborate selection process. Only applications of the highest scientific quality are chosen.

In principle, the facilities at PSI are just huge microscopes?

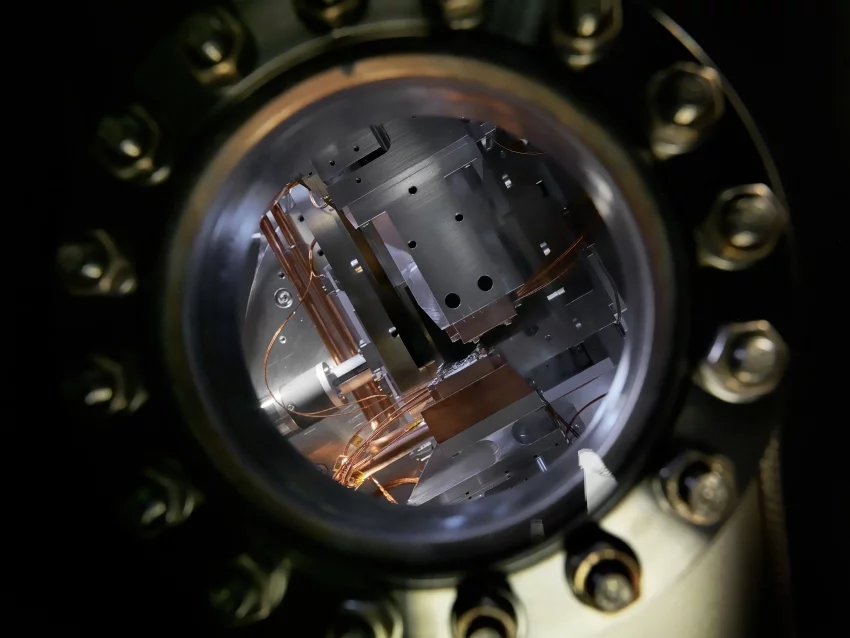

Yes, similar to what is done with an electron microscope, at PSI we can obtain information about tiny structures but with additional information about the chemical bonds in the samples under examination. Different equipment is required depending on the material and the investigation. At the Swiss Light Source (SLS), where I work, there are 18 beamlines. The Phoenix experimental station, which I am in charge of, is one of them.

As a rule, the scientists who visit you only have a few days to get their results?

Yes, this is an intense situation. Most of them measure continuously, working day and night, to obtain all the data they need in a short time. Occasionally I will have to say, “that’s enough for now; get some sleep for a few hours.” When a research team works in harmony, and, thanks to the measurements they perform here, make important progresses in their research, in the final stages, there is a euphoric mood – it almost feels as exciting as a moon landing.

Roughly speaking, when a researcher arrives to perform their measurements, what has to be done?

Most of our work is carried out in advance and is often behind the scenes. A technician prepares the appropriate mounts for the specimens. For weeks in advance, he will make drawings and build everything that’s required. Nevertheless, he sometimes has to improvise within a few hours because someone has submitted the wrong plans. An engineer works in the background on the electronics and maintains the detector. The detector is one of the centrepieces of our measurement station. It records the data from which we calculate the images our users need for their advanced work. Without my colleagues, quite often, I‘d get totally lost.

The Phoenix experimental station has not been in operation for a very long time, yet it’s overbooked already. What’s so special about it?

We can visualise how individual atoms are incorporated into a material. For example, we can determine how many atoms there are in the vicinity of another atom. We can also observe how a chemical element is bonded. Quite often we have samples from environmental research, and get involved in questions from this field. For example, arsenic or chromium is toxic in some compounds, yet harmless in others. Generally, we specialise in light elements such as sodium or magnesium. In the whole of Europe, only at PSI and in Paris one can see this level of detail. We occupy a niche market, so to speak. Even scientists from the USA travel to the PSI to use our system.

Do you stay in contact with the users once their experiments are complete?

We view the data together at the end of, and sometimes during, their visit. The data analysis itself is hugely expensive. Often, collaborations result from user visits. We understand the experimental conditions under which the experiments have to be conducted, whilst the visitors are specialists in their fields of research. So we are constantly learning from each another.

With such a tight timetable, how do you manage to always have everything ready for the next research group?

We carry out the modifications at the beamline between groups. In the background, tests and developments are being performed continuously for the next groups. For about one-third of the groups who come here, we have to develop specific solutions.

What would a “routine” experiment be?

The routine experiment is...that there is no such thing as a routine experiment. Sure, there are default experiments that our station is designed for. However, in practice, experiments like this are only performed once every few months. For us, these are relatively relaxing days.

How do you see your role in the research activities?

We beamline scientists are actually researchers with a service function. For this job, you occasionally have to be a “physicist with the excessive need to help others.” Our work is a balancing act between our own research and operating a service for our visitors. It’s great if good cooperation results.

Although Phoenix already has three times more requests than you can cope with time-wise, there are still lengthy periods without any user operations.

The operation of the SLS is regularly interrupted so that service and maintenance work can be carried out on the source. At Phoenix, we also have to share the X-ray light source with another group, so the experimental station is only at our disposal for about half the time.

What do you do in the months when there are no user operations?

We use the time for extensive testing and work on improving the station. We also need to monitor the market constantly, to make sure we stay up to date technique-wise – after all, we have to compete with the other Synchrotrons in Europe, and we have a very good reputation to maintain.

You built the Phoenix measurement station in 2007 and it’s been in operation since 2009. How much time do you have for your own research?

The beamline scientists get about 30 percent of the time for their own research. However, when users are here, everything else takes a back seat. Amongst other things, my research focuses on how particles are formed by precipitation in liquids. It’s a fascinating and varied topic - just like all of my work here.

Personal Details

Physicist Thomas Huthwelker studied in Bonn and obtained his Doctorate in Mainz. He was a postdoctoral student at ETH and from there, joined the PSI in 2004. He was responsible for the development and installation of the Phoenix experimental station and provides support as a beamline scientist there. At the PSI, he conducts research in the field of surface chemistry and supports visiting scientists and academics during their experiments on Phoenix.Additional information

Beamline Phoenix at the Swiss Light Source SLSUser Office The PSI User Office is a central PSI installation to serve the users from all the four user laboratories.