Martin Ostermaier wanted to break out of the comfort zone of science. Now, instead of pipettes, the biochemist is dealing with investors and patent law.

Martin Ostermaier, a 33-year-old Bavarian with rimless glasses and curly dark-brown hair, sits in the cafeteria of the eastern campus of the Paul Scherrer Institute, occasionally jotting something down in a black notebook in front of him. I believe we have convinced them

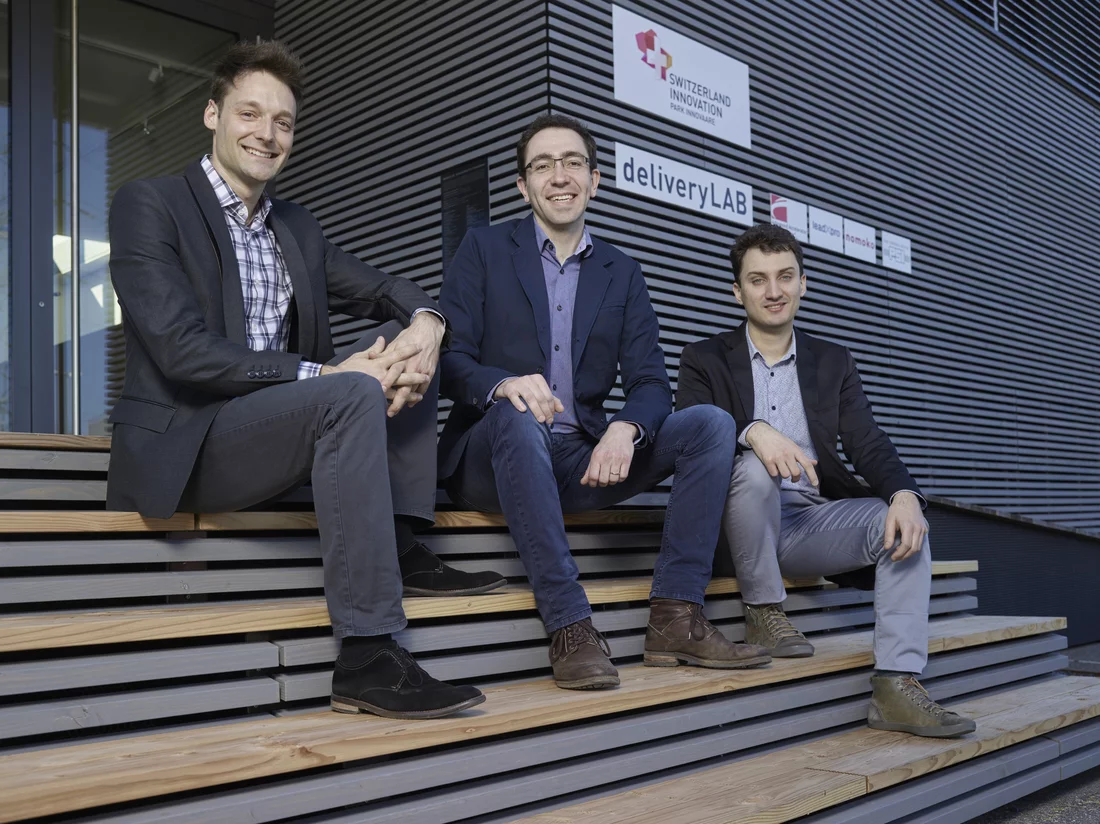

, states Ostermaier, a PhD biochemist and CEO of the PSI spin-off InterAx Biotech AG.

How much do they want?

, asks Prof. Jens Gobrecht, head of the Laboratory for Micro- and Nanotechnology, who represents the Institute on the management board.

Last week, two potential investors from overseas visited the spin-off, and now they have set their terms for the initial investment. Ostermaier reports what equity share they are demanding in return for this investment.

Try to bargain with them

, Gobrecht advises. How much salary do you want to pay yourselves? Investors don’t like to see their money spent on lavish salaries.

Next to Ostermaier sit Luca Zenone and Aurélien Rizk, the two co-founders. What they had in mind was a greatly reduced postdoc salary, replies CFO Zenone.

Gobrecht says that would be modest, in his opinion. They continue a while longer discussing patent conflicts, the costs of good patent attorneys, and possible bonus payments. Then Gobrecht has to move on, and Ostermaier, Zenone, and Rizk start their 136th day as owners of InterAx Biotech AG.

From researcher to businessman

Since he finished his dissertation in 2014, Martin Ostermaier has completed the transformation from researcher to businessman. His firm is the latest in a series of Paul Scherrer Institute spin-offs dedicated to developing the basic research produced here into commercially viable products. Many researchers are afraid to take this leap into cold water. Yet Martin Ostermaier already seems to feel like a fish in this cold water. After all, he grew up in an enterprise. His parents ran a farm in the Bavarian town of Altötting. Ostermaier, the second of five children, had to pitch in at an early age. He helped with the sale of milk and other products at the farm and later drove the grain harvest to the silos, where he was responsible for drying, cleaning, and storing it. As a child, he learned about the business cycle of farming the hard way. At Christmas in the good years, there were so many presents that you could hardly get to the tree

, he recalls, and in bad years just one book.

His father, Ostermaier says, would naturally have liked to see one of his sons take over the business. But in spite of that, he always supported us in our academic path.

Already as a boy, Ostermaier wanted a chemistry set. Also in the family, presumably, lie the roots of his extraordinary ambition, which his business partners and advisors bear witness to. His older brother completed his Abitur,the secondary-school exams, at the top of his class. When my mother told me, you don’t need to be as good as your brother, that’s when I really started to want it

, Ostermaier says. Not only did he achieve that, but he also received a merit scholarship from the state of Bavaria.

At the nearby University of Regensburg, Ostermaier enrolled in the honours programme for biochemistry, which amounted to jumping into the shark tank. One time before the exams, the prep papers disappeared from the student union’s common room

, he says. In addition, the freedom-loving Ostermaier was bothered by the inflexible research climate. You had to stick strictly to the experimental protocol and got stern looks if you didn’t show up in the lab on time.

He still raves about his student exchange in Colorado. I could go to the lab when I wanted to, I could pursue my research freely, and in spite of the hard work I could spend a lot of free time together with my colleagues.

After graduation, he attended an ETH Zurich recruiting event for doctoral candidates. Ostermaier knows what he wants. When he saw that the professors available for interviews were not the ones who were supposed to be there, he was ready to leave. Then, however, he talked with Gebhard Schertler, who had recently been appointed to a chair for structural biology. Schertler convinced him to do his doctorate at the PSI on the topic of G protein-coupled receptors. Ostermaier is still enthusiastic about the support he received under the current group leader Jörg Standfuss. After the doctorate, Schertler wanted to place his protege in the elite American university Stanford. But Ostermaier didn’t want that. I wanted to get out of the comfort zone of science

, he explains. There the career would be competitive indeed, but predetermined. As an entrepreneur, on the other hand, he’d have no idea what might lie in store.

Facilitating the search for the best active agents

With his receptor research, Ostermaier wanted to develop biosensors for the search for the active agents of pharmaceuticals, so that those substances with the best chance of success in clinical studies could be selected at an early stage. He competed successfully for a Pioneer Fellowship of ETH Zurich and was awarded 150,000 Swiss francs to use, over the next 18 months, for further development of his research on receptors. At VentureLab, an ETH Zurich course for researchers who want to found a spin-off, he met the mechanical engineer and trained business manager Luca Zenone. He recalls Ostermaier’s first presentation: It was all too technical and detailed. The big picture was missing

, Zenone says. But he was very enthusiastic.

And, adds Zenone, he showed a strong will to learn new things. Since that time he almost has to take care not to act too much like a businessman during presentations in front of researchers

, notes Grego Cicchetti, who as a science relations manager at the PSI provides assistance to spin-off companies.

At noon the three young entrepreneurs go, as usual, to the staff restaurant on the eastern campus. Zenone and Rizk take the lunch menu, while Ostermaier eats spaghetti out of a Tupperware container. Ostermaier lives with his wife and their two small children in Waldshut just across the border in Germany, also to economise. At present the three are still working for doctoral candidates’ salaries. In business they would earn many times more. But here they are their own bosses; that’s probably why, after a few minutes of office gossip, they are again back to business. During the coffee break the young men get very excited. Zenone holds his mobile phone under Ostermaier’s nose. The potential investors have sent a draft of the term sheet. Now sealing the deal might be little more than a formality. Even Ostermaier who, according to Zenone, sometimes gave only terse answers during the hectic weeks of the search for investors, is beaming. With this money, they would finally be able develop their biosensors to the point where they are market-ready. Even if it weren’t to grow exponentially

, says a relaxed Ostermaier on the terrace, InterAx is a success now already — for Switzerland too. We will spend the funds mainly here.

However, the more successful InterAx becomes, the less control Martin Ostermaier will have over his firm. With every investment, the founders’ own share decreases. At some point the investors could decide to sell InterAx. Ostermaier shrugs his shoulders — in that case, there’s nothing he could do. If I make it possible for myself and other people to do what we love for a couple of years, I’ve achieved my goal.

Aurélien Rizk and Luca Zenone are already back in the office. Martin Ostermaier gives a friendly smile but is already tapping his foot impatiently, like a player on the bench. He wants to get back to work.

Text: Joel Bedetti