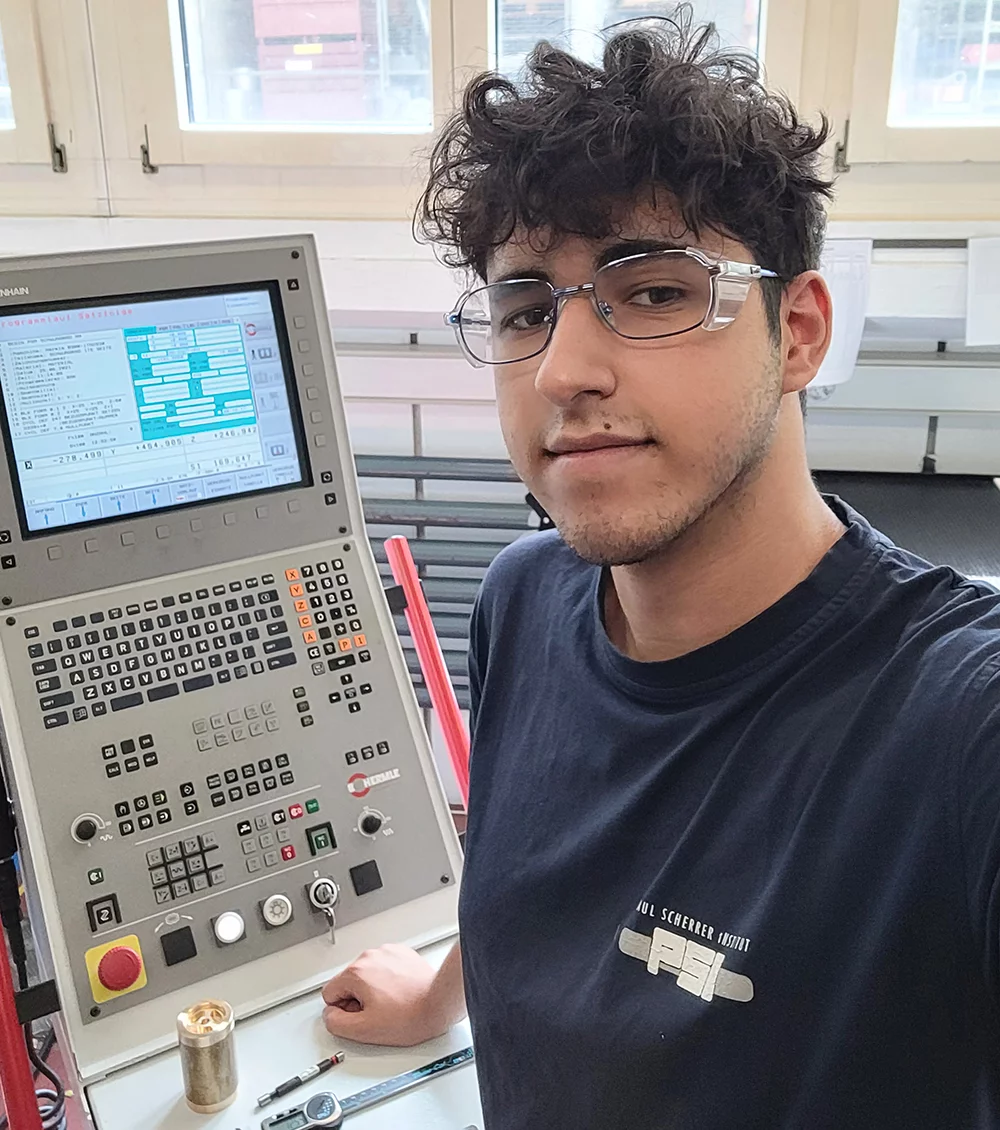

After finishing high school, Rohat Sihyürek joined PSI as an apprentice polymechanic. There, the 20-year-old manufactured high-precision parts that are essential for Switzerland's largest research facilities.

Rohat Sihyürek: "At school, I wasn't particularly interested in natural sciences. But when I saw the PSI research facilities for the first time, I was completely fascinated. They are really impressive. I knew I wanted to do something with my head as well as my hands, and that would result in tangible things I could be proud of. What the people at PSI do and the goals they pursue convinced me to do my Polymechanic apprenticeship here.

I have been at PSI since 2017. I mill, turn, drill and cut to produce special metal parts that are used for the maintenance or development of PSI's large facilities: SwissFEL, SINQ (editor's note: the spallation neutron source), the Swiss Light Source. Most of the time, these are one-off orders or very small numbers. The quality requirements are very high: the parts must be flawless, extremely smooth and produced with millimeter precision. At first, this was a challenge. But at PSI, the apprentices have time to train and improve – it's the quality of the work that counts, not the quantity. I learnt a lot from the feedback from my apprentice master about what to improve and what techniques to practice.

I think our work is important to make these research facilities work, but we have little contact with the scientists: the orders come from the manufacturers. I do follow what is going on at PSI through the newsletters or by attending presentations of new projects. The scientists speak in a complicated way, it is sometimes difficult to follow them, but in general you get a basic understanding of the project.

To be hired at PSI, I had an interview and an aptitude test. I was able to show my strengths: mathematics, geometry and English. I saw that learning is taken seriously, and this was confirmed. We can take many courses, for example CAD technical drawing, specialised welding, automation or pneumatic controls. The courses at PSI are not only theoretical, like those at the vocational school, but also very practical. I learned a lot here, also about the human aspects – how to treat your colleagues, how to motivate yourself, how to improve yourself. My trainer always says: now is the time to fill your backpack and learn as much as you can.

I'm in my fourth year and I'm finishing this summer (Editor's note: The interview took place before the summer holidays). After that, I'd like to work in large industrial plants, in the automotive or precision watchmaking industries. Or, why not, continue in a research institution. I've really enjoyed my time here.

Text: Daniel Saraga

Article based on a text from sciena.ch

Apprenticeship – the hidden face of Swiss research

Apprentices play a little-known but essential role in science made in Switzerland. Here, we take a look at young people who are being trained in the institutions of the ETH Domain.

From the laboratory to construction, from electronics to polymechanics: some twenty professions are taught in the institutions of the ETH Domain. These different professions play a key role in the scientific advances that have made Swiss research internationally renowned. "Our apprentices work on very specific research projects," explains Stefan Hösli, head of apprenticeships at Empa. "Some conduct experiments alongside our scientists, others manufacture complex parts for all kinds of devices and installations. They are also players in Swiss research, but they are scarcely visible."

Céline Henzelin-Nkubana, head of the apprentice laboratory school at EPFL's Institute of Chemical Sciences and Engineering, points out that the Swiss dual training system is not well known to the many foreign scientists working in Switzerland: "They often underestimate the capabilities of the young people we train. Every year, I look for research groups to supervise the eight new apprentices who join us, and I sometimes observe some reluctance on the part of the professors. But next they are very surprised when they see the quality of the work done. Our apprentices spend a year and a half perfecting laboratory techniques and are often very fast, efficient and meticulous."

The different worlds of apprenticeship and research do not always see eye to eye with each other , continues the chemist. One group leader had ignored an apprentice for months during the weekly meetings, but he finally integrated her: after talking to her once alone, he realised that she knew a lot more than he had imagined. In order to better integrate these two worlds, the EPFL has entrusted the management of the Laboratory-School to a duo: "I have had a career in academic and industrial research, while my colleague did an apprenticeship followed by studies at a university of applied sciences and a spell in the private sector."

Apprentice and author of a scientific article

Some professions – such as laboratory assistants in chemistry, physics and biology – are well integrated into research groups. Young people prepare and conduct experiments under the supervision of PhD students. These contributions are generally recognised, for example in the acknowledgements at the end of scientific articles or during presentations. Sometimes apprentices are even listed as co-authors, a nice recognition of their contribution to research.

Other professions have more distant links with the academic world. "We usually receive orders from manufacturers and it is they who talk to the scientists," says Markus Fritschi, a polymechanics trainer at PSI. But these apprenticeships are also influenced by the research environment: "Our apprentices work on very special parts in small numbers – in contrast to industry, which generally produces large quantities in a more standardised way," says Stefan Hösli of Empa. “We have a great deal of freedom in what we teach them, and of course we work with state-of-the-art technology which is not always available in vocational schools. In fact, we are in discussion with the professional associations about how we can speed up the development of vocational education by integrating modern tools such as 3D printing."

Curious, open-minded and talented young people

The young people who do their apprenticeship in the research institutions of the ETH Domain have a special profile, say the trainers: curious people who are interested in both manual work and thinking and who are not afraid of a challenge. "There is a small – but growing – number of women," says Cornel Andreoli, trainer of physics laboratory assistants at ETH Zurich.

The paradox is that these young talents often end up leaving their basic profession to pursue higher education. "On the one hand, I am delighted to see apprentices continuing their education at university. On the other hand, these are talented people who will be missed in our profession," says Stefan Hösli. A real hand drain, to echo the famous brain drain of academics who leave their country of origin. Only a quarter of these chemical laboratory assistants remain in the profession, confirms Céline Henzelin-Nkubana, with a quarter changing direction slightly and a good half going on to higher studies. "At the beginning, most of them say they want to work and not study. But these research experiences often trigger a change of direction – and create new vocations."

Text: Daniel Saraga

Article based on a text from sciena.ch

Additional information

Vocational Training at the Paul Scherrer Institute PSI

Copyright

PSI provides image and/or video material free of charge for media coverage of the content of the above text. Use of this material for other purposes is not permitted. This also includes the transfer of the image and video material into databases as well as sale by third parties.